Reading in Your Target Language Can Boost You to Fluency – Here’s How!

Are you a reader? Do you feel a bit too giddy anytime you enter a library? Do you take a book with you wherever you go?

Your answer to any or all of these questions may very well be no. And that’s okay!

What I want to show you today is that reading, besides something you may chalk up to something you “should do more often”, is really quite an exciting and effective language learning tool. Whether you’re looking at comic books or romance novels, celebrity tell-it-alls or short stories designed for language learners, you’re doing something uniquely effective when you read in your target language.

If you don’t believe me, hear what Stephen Krashen, famed second language acquisition expert, has to say about it: “(More recent studies in second language acquisition) report a positive relationship between the amount of free reading done and various aspects of second and foreign language competence when the amount of formal instruction students had is statistically controlled.”

In other words: free reading can boost you beyond the progress you make with traditional language instruction.

Why is that?

Improving Your Sprachgefühl

My opinion is that reading in your target language improves your overall Sprachgefühl, or the ability to intuitively understand grammar structures and vocabulary. This gives your brain a large base of subconscious passive knowledge to work from, giving you an advantage in the active language domains and therefore boosting you to fluency.

In other words, where traditional language learning gives you bits and pieces, reading provides a comprehensive, base-level knowledge that provides a sturdy foundation to your language awareness.

I believe an important distinction to make is the difference between vocabulary knowledge and reading comprehension. These are related skills, but nonetheless not the same. One can develop one’s overall reading comprehension, eg. how much one can understand a given passage, without necessarily actively learning more vocabulary.

Here you could go into semantics about what it means to “learn” a word, but what I’m looking at is something more general: when you improve your reading comprehension, you’re improving your brain’s ability to parse sentences, to identify the different parts of a sentence.

Even if you don’t understand the words, you can make better guesses because your brain understands the different “slots” parts of a sentence fit into, the different forms a given sentence or paragraph can take.

There is a huge difference between a sentence whose structure you understand (what part is an adverb, what part is a noun, how these parts interact with each other) and a sentence where you cannot identify the parts, much less the relationship between these parts. And I believe that an intensive approach to reading (more on that later) gives you the best chance of improving this so-called Sprachgefühl.

When you read, your brain receives infinite context, like this post notes.

Reading Time in Action – How Does it Work?

Let’s take the example of 成語 (chéng yǔ) in Mandarin. These are phrases made up of four characters that have idiomatic meanings. They often have a basis in more classical forms of the language. Mandarin learners often see these set phrases as ways to boost their language level and control a more elevated style of the language.

I want to use these as an example because I believe they provide a great illustration of what reading comprehension can do for your understanding.

Sometimes, people learn these phrases through traditional instruction. Perhaps they learn them through a book of idioms that lists different 成語. These sources are not necessarily context rich. You may get one example sentence, but I believe that’s not enough: the context is not wide enough for you to understand how to use it. And if you just learn the four characters without even a sentence to go off of (which I have experienced), your chances of remembering it, much less using it correctly, are slim.

But when you read one and learn it that way, you’re surrounded by pages of context. You know what precedes its usage just as you can see what comes after it in the context of what you’re reading.

For me, increasing my reading time in Chinese has meant being able to internalize more deeply 成語 that I learned before, but never quite understood how to use naturally. Through repeated intensive reading, I’ve seen certain ones pop up multiple times, which makes me a much more confident user.

That Pesky Subjunctive

Another example that illustrates the benefits to reading well is the subjunctive tense.

I know that when I first started learning Spanish, which was the first foreign language I studied seriously, I found the subjunctive tense quite tricky.

Teachers would list rules in generic ways and give an example sentence here and there, but it wasn’t enough. The blocks in my brain did not click in the way that would have me truly understand in what contexts the subjunctive could be used, and where it was to be avoided.

One could compare this type of approach to searching for a needle in a haystack. Learning a few simple rules, with just a couple of examples to guide you, is barely scratching the surface of the usage, and you’ll never learn to use it confidently if you don’t have enough input. You have to drill your brain with a wealth of examples in order to truly grasp the concept.

This is another example of where reading comprehension is so powerful for fluency. Instead of taking the subjunctive tense and trying to deduce where you can use it, you’re inducing from every single example you see in the text. Each example is a piece of the puzzle, some very large almost interminable puzzle, where every piece leads to a more complete understanding.

The more you read, the more your brain will intuitively understand its usage.

What to Read?

So hopefully, by now, you can start to see why I am such an advocate of reading in a language learning routine. But what to read? Should I read materials made for language learners, or try out content made for native speakers? What genres? And how difficult should it be?

First of all, I should clarify that reading in your foreign language does not have to mean reading a traditional novel. Comics, manga, newspapers, magazines and even cookbooks can be great resources! What’s most important is to choose something that will engage you and keep your interest.

If you have specific goals in mind with your reading comprehension, you should keep those in mind, too.

For me, my plan is to study for a Master’s degree in Chinese literature. To prepare myself for the rigors of that program, I primarily seek out works in Mandarin that are relevant to my research interests (namely, researching the connection between Marquez’s magical realism and the Chinese novel in the late 20th century.)

This, of course, also spreads to my Spanish reading goals, as I want to read as much Marquez as possible.

I see my ability to read Marquez in his original language, a Latin American author whose influence on the Chinese-speaking world is quite remarkable, as a great asset to my studies. It is also true, however, that sometimes I need to read something less taxing.

When I started reading in Chinese, I read a Murakami novel, completely irrelevant to my research interests and not even of the Chinese-speaking world, but great fun and a great way to build my confidence as a reader.

So, when choosing materials, don’t forget to think about your goals. What do you want to be reading with more fluency and increased comprehension in the future? Just as importantly, what type of reading materials will best keep you engaged for your goals?

I recommend taking a similar approach to children learning to read in their native language. Did you have experiences in a library as a child? Do you remember the excitement of being able to pick from a variety of books, each time understanding a little deeper what you liked and what you didn’t like?

Starting as a reader in your native language can be like that, too: each language stems from a different literary tradition, with different reading habits and tastes, and with differing amounts of materials available in your home country.

For a while, I struggled to find books in German that piqued my interest. Even when I got an e-reader, a purchase that greatly expanded the books I had access to, I had trouble finding books that I wanted to read. When I first began trying out works of fiction from the German canon, I couldn’t find books that matched my tastes. I had to do a lot of experimenting and trial by error to finally discover my tastes as a German reader. This is why I emphasize that in each language, you will have to make an effort to find your reading identity.

In order to find your reading identity, you may have to go through a lot of material, which may not be accessible to you where you live, depending on the language you study. But with some creativity and some luck, you can find materials for any language.

While I previously noted that my e-reader is a huge help, I also have a soft spot for books I can touch and hold in my hands: there’s something about the book as an object that makes me excited about reading.

When I moved to Taiwan especially, I couldn’t find anything in German in any bookstores and had partially given up on the idea of finding physical copies.

That is until I discovered the Goethe Institut in Taipei.

Coming off a suggestion from a Facebook group, I discovered this oasis of German literature. The first time I visited, it was like magic: here I was surrounded by a great range of German books, from novels to biographies to children’s books, all in great condition and for free.

I also recently found a similar program from the Instituto Cervantes, where I can read from their extensive library of Spanish books for just 15 euros a year.

When there’s a will, there’s a way: no matter how little material is available for your language or where you live, I know there’s a way you can find enough material to support your success as a growing reader in your target language.

Difficulty is also an important consideration.

Some people might tell you that you should be reading material that you understand 95% of; otherwise, you’re wasting your time. I’m not necessarily of that mindset. With my first Chinese novel, my comprehension did not reach that high. It was probably closer to 80 or 85%. But because I was enjoying the material, it was a great reading experience.

All in all, choosing a novel when you’re just at an A1 level may just be intimidating, but you always have the option to shoot a bit above your level if the content is interesting to you.

Igor, a previous guest blogger, recommends a comparative reading strategy, which I believe is a great idea to supplement your understanding: you read the book in its target language alongside a translation in your native language.

This can give you access to works at an earlier stage in your language process, since you can always look at the translation to clarify meaning. It’s also a great tool to quiz your understanding at any stage.

As I am reading Chinese literature partially for its content, I think I’ll try this method next time!

How to Maximize Your Learning

In order to maximize your learning and boost the effect, you should be intentional in your reading methods.

One important aspect of your method to consider when beginning a book in your target language is the difference between an intensive and an extensive approach. You may have heard these terms before, but just in case you’re unfamiliar, I’ll explain: an intensive approach focuses on quality, and an extensive approach focuses on quantity.

When you read intensively, you look up as many words as possible, you seek to understand every part of the text. On the other hand, when your approach is extensive, the idea is to read as much as possible: in a purely extensive approach, you may not look up anything.

I don’t bring up this distinction to support one approach over the other; in fact, I believe a mix of both is the best approach for optimal language learning.

It is important to note that these approaches exist on a spectrum: you can control the amount of words you look up or the level to which you want to study the text according to your goals.

That being said, how can you make this decision regarding a specific reading material?

I’ll start by giving some examples from my reading life.

I recently read my first full novel in Chinese (now, I’m on my fourth!)

I had read news articles and other short pieces before, but never a full book. It really intimidated me: even though I began studying German after I began Chinese, my Chinese reading lagged behind my German. There are linguistic reasons for this, but most importantly, my biggest hindrance was my own fear.

When I looked at a Chinese book, I panicked at all the words I not only did not understand, but couldn’t even pronounce! I always took one panicked glance to decide I wasn’t ready.

But with that mindset, you’ll never be ready. I decided one day, when I got serious about my goal of studying for a Master’s degree in Chinese literature here in Taiwan, that something needed to change. I just had to settle down and do it: I was tired of waiting until I was “ready,” my biggest barrier was my own lack of confidence.

Considering my high amount of anxiety around the subject as well as it being my first book in Chinese, I decided to pick a book from Haruki Murakami (Sputnik Sweetheart for those who may be wondering!).

Although my ultimate goal was (and is) to read Chinese works relevant to my studies, I chose this book as a way to increase my confidence reading in Chinese. I had already read several Murakami novels in English before, and I was familiar with the way his plots tend to develop, so I felt this would give me the best chance to both understand as much as possible and enjoy the experience.

For my first Chinese reading experience, I also made the decision to look up zero words.

That’s right: zero.

I wanted to take an exclusively extensive approach because I knew that reading the book in and of itself was going to be a challenging task, and I knew with my personality that, if I required myself to look up a certain amount of words, I would get discouraged.

I was like a child defiantly reading a book an adult had told me was above my level: I went into it accepting that there would be sentences I couldn’t handle, perhaps entire pages that I felt lost in. And that was okay, because it would mean that I would finish.

And finish I did!

Interacting With the Text and Extending Your Learning

When I say I used an exclusively extensive approach, that doesn’t mean I didn’t use reading strategies to aid me in a sea of Chinese characters. If you take a look at this previous post by Janina Klimas, you’ll see that good readers use a wide variety of different strategies to interact with the material and understand it more deeply.

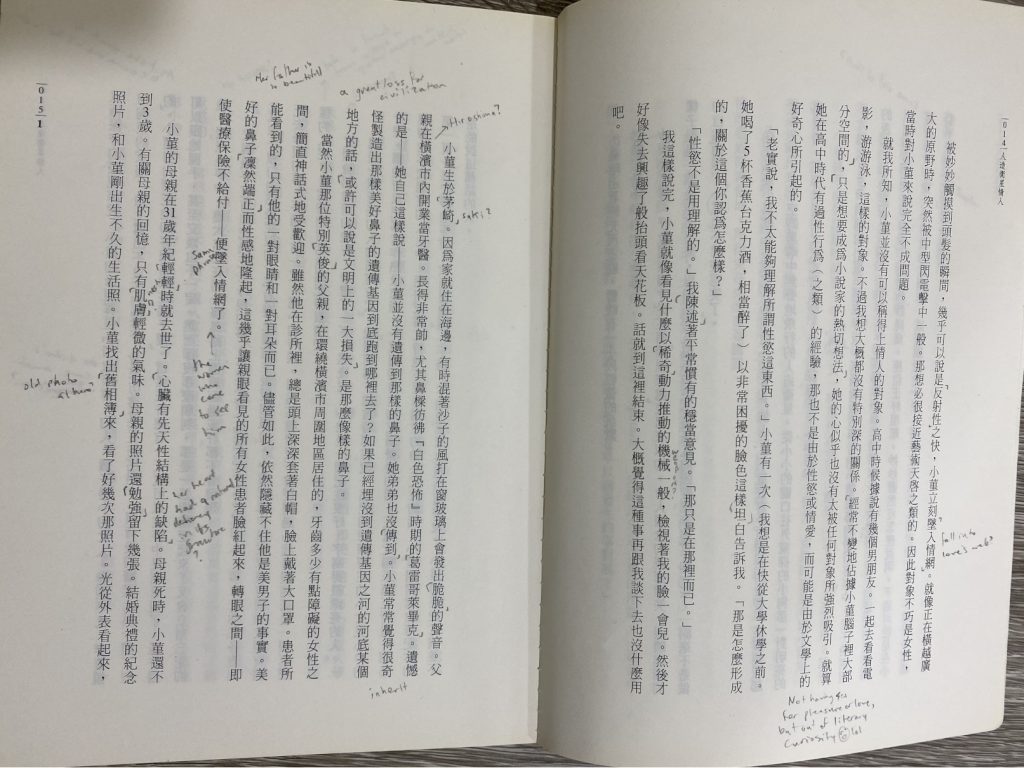

Here’s an example of a page from my Murakami paperback:

When I annotate, I do a few different things.

I react to the story with notes in the margins: to a character whose personality rubs me the wrong way, to a situation I think is funny.

I acknowledge where I am confused: I write questions, put brackets and question marks around sentences I just don’t understand, even after rereading. I put brackets around vocabulary words that I don’t know to mark them for the post-read vocabulary list I usually make.

And just as importantly, I give “likes”: the writer in me highlights sentences I find particularly beautiful or insightful, always looking for inspiration in the craft of others. I may even draw a little heart where I think something is cute.

You can decide whether you want to write your notes in your native language, in your target language, or in a mix. I usually annotate in English for Chinese books because my character handwriting leaves something to be desired.

After I finish reading, I usually do some sort of extension activity to reinforce my understanding of the book and the vocabulary I’ve learned. I look at the vocabulary words I’ve set in brackets, and I make a list of about 25 words with their definitions.

I limit myself to this number because if I wrote every word down, I would lose motivation and never finish, and also because I don’t think it would be productive to try to learn too many words at once.

When I finish making a word list with definitions, I also may decide to make flashcards.

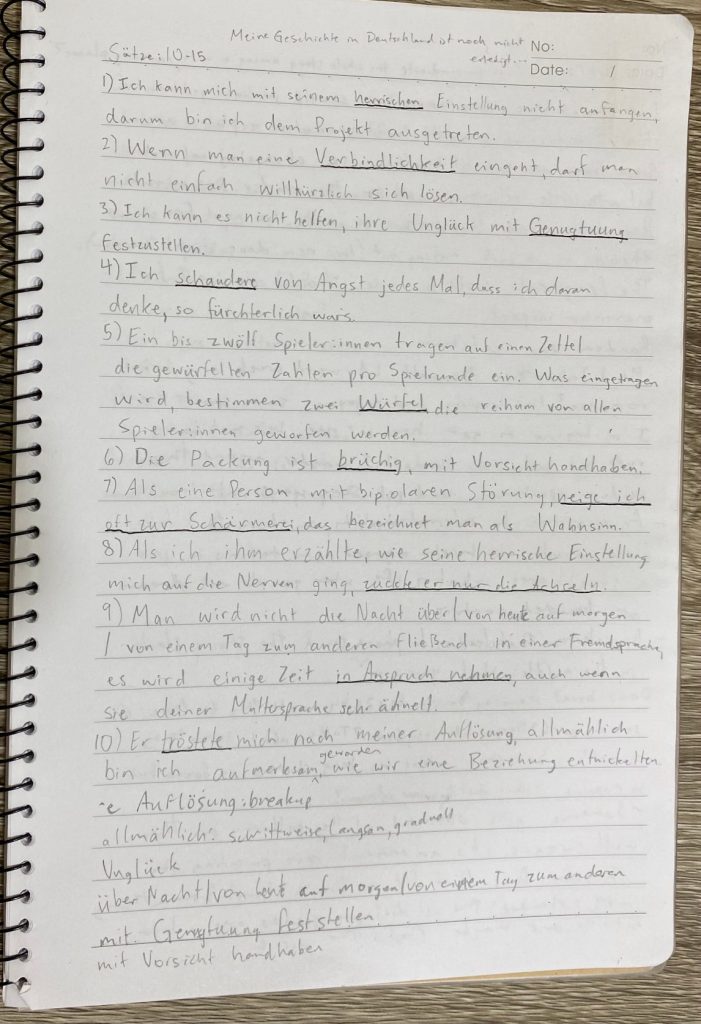

The flashcards I recently made for the last German book I read are currently sitting on my living room table, easy access for me to review whenever I have a minute. I also sometimes make sentences, though to tell you the truth I sometimes run out of steam before I get to that point…

These are sentences I wrote based on vocabulary words in a German novel I read recently, Blaupause. At the bottom, I wrote phrases that I had to look up while writing my sentences. Writing sentences is a great way to make passive vocabulary knowledge more active!

Well, these are all my tips! I hope you’ve learned something or been inspired to boost your fluency through reading.

Social