Learn the French Pronouns Once and For All [With Charts!]

Pronouns in French are a bit different to English. If you’re a new French learner, pronouns might seem confusing or intimidating at first, but I promise there’s a logic to them that makes them pretty easy to learn.

This article is a comprehensive guide to every type of pronoun in French. We’ll cover everything you need to know for mastery of les pronoms français.

Table of contents

- French Pronouns: The Basics

- French Personal Pronouns

- French Subject Pronouns

- French Direct Object Pronouns

- French Indirect Object Pronouns

- The French Adverbial Pronouns Y and En

- French Reflexive Pronouns

- French Pronoun Order

- French Stressed Pronouns

- French Possessive Pronouns

- French Relative Pronouns

- French Demonstrative Pronouns and Determiners

- French Interrogative Pronouns

- Resources to Learn French

You don’t need to learn all of these rules at once. Start with the basics, and treat this guide as a reference to come back to when you need it.

French Pronouns: The Basics

The word pronoun means “in place of a noun”. Without pronouns, our sentences would be repetitive and boring. We’d have to say things like, “Sarah wasn’t watching what Sarah was doing and Sarah spilled wine over Sarah’s shirt.”

You can make that sentence a lot more natural by replacing “Sarah” with pronouns: “Sarah wasn’t watching what she was doing and she spilled wine over her shirt.”

Adding the right pronouns to your French sentences will make them sound a lot more natural and fluent, too!

To keep things organised, let’s look at French pronouns one type at a time.

French Personal Pronouns

The French pronouns you’ll use the most often are the personal pronouns. They work just like English pronouns like “I”, “she”, and “them”. They come in a few different flavours.

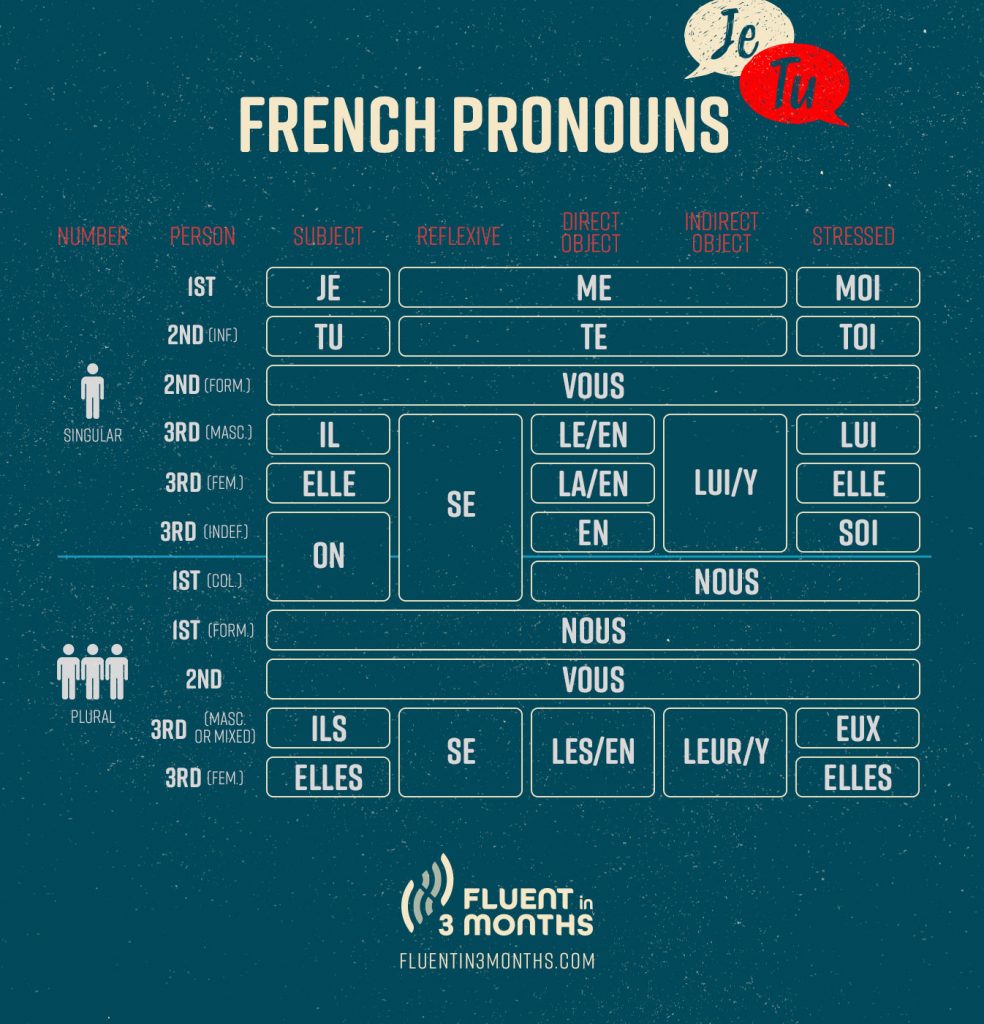

If you just want the full French personal pronoun chart, here it is:

French Subject Pronouns

The most basic French personal pronouns are the French subject pronouns. They’re used for the subject of the sentence; that is, the person or thing who’s doing the action in the sentence.

| je | I |

| tu | you (singular) |

| il/elle | he/she |

| on | (see below) |

| nous | we |

| vous | you (plural or formal) |

| ils/elles | they |

Here’s what the subject pronouns look like in action:

- je parle – “I speak”

- tu parles – “you speak”

- il/elle/on parle – “he/she/one/we speak(s)” (a bit more on this one later)

- nous parlons – “we speak”

- vous parlez – “you (plural or formal) speak”

- ils/elles parlent – “they speak”

Je abbreviates to j’ before a vowel sound:

- J’ai mangé – “I’ve eaten.”

Use il for men and elle for women. When referring to a group of people, use elles for an all-female group, and ils for an all-male or mixed group.

French doesn’t have a direct equivalent of the gender-neutral pronoun “it”. Instead, when talking about objects, use il for masculine nouns, and elle for feminine.

- La voiture est rouge / Elle est rouge. – “The car is red” / “It is red.”

You can also use il in impersonal expressions, or to mean “it” in an abstract sense.

- Il pleut – “It’s raining.”

- Il est possible que… – “It’s possible that…”

Tu vs. Vous in French

English is weird in that we have one pronoun for both the singular and plural “you”.

“You” can be said to a single person or a group. Depending on your dialect, you might also address a group as “you guys”, “you lot”, “yous”, or “y’all”.

French, on the other hand, has two words for “you”. Tu is used to informally address an individual. Vous is used to respectfully address an individual, or to address a group of people at any level of formality.

Tu is considered colloquial and informal. Use tu when talking to friends, or to someone who’s equal to or lower than you in status or seniority, for example as a teacher speaking to a student.

When talking to adults in formal and professional situations, and especially when speaking to someone senior or higher status than you, it’s generally expected that you use vous.

Calling someone tu when they expect vous can be considered impolite. It’s best to err on the side of politeness and stick with vous, at least at first. French speakers are very familiar with the social game of figuring out the right formality level to use, and most will simply come out and tell you if they prefer tu over vous.

And don’t forget: all of this only applies when speaking to an individual. When addressing a group, you always use vous.

How to Use the Pronoun On in French

On is an unusual pronoun that has two main meanings.

First, it can be used as an indefinite pronoun, referring to an unspecified, general person. You could translate this into English as “you”, “they”, “someone”, or, if you’re feeling posh, “one”.

- Réponds si on t'appelle! – “Answer if someone calls you!”

- On me l'a donné – “Someone gave it to me.”

- On ne sait jamais – “You never know.” or “One never knows.”

You can also use on in this sense to avoid the passive voice.

- On lui a demandé de partir – “He was asked to leave” (literally: “they/someone asked him/her to leave.”

The other main meaning is not found in English.

In informal or everyday speech it’s very common to use on instead of nous to mean “we”. So the sentence “we are learning French” can be translated as on apprend le français instead of nous parlons français.

Note that on always takes the same verb endings as il/elle, even when it means “we”. This means that it’s on parle, never on parlons.

But when on is being used to mean “we”, adjectives should have plural endings:

- On est canadiens – “We’re Canadian.”

(Etymological trivia: on is a distant cousin of the French word homme, which means “man”.)

Sometimes, when on comes after a word that ends in a vowel sound – in particular after et, ou, où, qui, quoi, and si – on is replaced by l’on.

The extra l doesn’t mean anything. It’s just there to make things sound better, by stopping the vowel sounds from running into each other:

- Et l'on pourrait dire que… – “And one could say that…”

- On n’est jamais content là où l’on est – “We (general ‘we’) are never happy where we are” (a well-known line from Le Petit Prince)

You don’t have to replace on with l’on. It’s rather old-fashioned, and is more common in writing than speech.

French Direct Object Pronouns

The direct object of a sentence is the thing which the verb is being done to. The French direct object pronouns are really straightforward:

| me | me |

| te | you (singular informal) |

| le | him, it |

| la | her, it |

| nous | us |

| vous | you (plural, or singular formal) |

| les | them |

Me, te and le abbreviate to m’, t’ and l’ before a vowel sound.

Unlike in English, French direct object pronouns go before the verb (but after the subject pronoun):

- Elle le connaît depuis cinq ans. – “She’s known him for five years.”

- Je t’aime – “I love you.”

- Nous vous voyons.* – “We see you.”

French Indirect Object Pronouns

Indirect objects are best explained by example.

Consider the English sentence “I kicked the ball to David.” It’s pretty clear that “the ball” is the direct object of the verb “to kick”; it’s the ball that my foot made contact with.

But my kicking also does something “to” David, indirectly: it makes him receive a ball. David is the indirect object of the verb.

Indirect objects are often indicated in English with the word “to” or “for”.

The French indirect object pronouns look like this:

| singular | 1st person (je) | me |

| 2nd person (tu) | te | |

| 3rd person (il/elle) | lui | |

| plural | 1st person (nous) | nous |

| 2nd person (vous) | vous | |

| 3rd person (ils/elles) | leur |

Notice that these are mostly the same as the direct object pronouns. The only differences are the third person singular (lui instead of le and la) and plural (leur instead of les.)

Indirect object pronouns go before the verb, and before the direct object pronoun if there is one:

- Il te donne un paquet – “He gives you a package” (or: “He gives a package to you”)

- Je leur explique – “I explain to them”

- Nous lui avons acheté un repas – “We bought him/her a meal” (or: “We bought a meal for him/her”)

- Tu me l’as donné hier – “You gave it to me yesterday” (notice how the indirect object pronoun me comes before the direct object pronoun le)

Watch out! Sometimes, the French verb takes an indirect object where it would be a direct object in English:

- Elle lui téléphone une fois par semaine. – “She phones him once a week.”

We say lui in this example instead of le because in French you don’t “phone someone”, you “phone to someone”: Je téléphone à Pierre.

On the other hand, sometimes French uses a direct object where you might not expect it:

- Où est ma veste? Je la cherche. – “Where’s my jacket? I’m looking for it.”

Since the English expression is “look for it”, not “look it”, you might expect to need an indirect object pronoun in French. But chercher takes a direct object, so we use la in this case, not lui.

The French Adverbial Pronouns Y and En

The French adverbial pronouns are y and en.

Usually, y replaces a noun that comes after the word à, while en replaces a noun that comes after de.

(To help remember this rule, just keep in mind that y and à both have one letter, while en and de both have two.)

Y

Y is most commonly translated as “there”. Use it to replace à plus a location:

- Allez-vous à la gare? Oui, j’y vais. – “Are you going to the train station? Yes, I’m going there.”

- Ils vont au musée (“They go to the museum”) → Ils y vont (“They go there”)

Or to replace à plus a noun that doesn’t refer to a person:

- Je pensais à mon livre. (“I was thinking about my book.”) → J’y pensais. (“I was thinking about it.”)

While y usually replaces à, it can be used for any preposition of location, such as chez (“at the house/business of”), dans (“in, inside”), en (“in”), sous (“under”), or sur (“on”):

- Je serai chez toi. (“I’ll be at your house.”) → J’y serai (“I’ll be there.”)

Y also shows up in some common expressions:

- Il y a – “There is”

- On y va! – “Let’s go!”

- Allons-y! – “Let’s go!” (same as on y va)

As I hinted earlier, y can’t be used to refer to a person. It also can’t replace a construction with à + a verb.

- Je réponds à Amélie. – “I’m responding to Amélie.” (correct)

- J’y réponds. (Not allowed to replace the above sentence!)

- J’ai hésité à donner mon opinion. – “I hesitate to give my opinion.” (correct)

- J’y ai hésité (wrong!!!)

En

En replaces de + noun:

- Je ne bois pas de bière (“I don’t drink beer.) → Je n’en bois pas. (“I don’t drink any of it.”)

- Elle ne veut pas parler de son travail (“She doesn’t want to talk about her job.”) → Elle ne veut pas en parler (“She doesn’t want to talk about it.”)

- Il est sorti du restaurant (“He left the restaurant.”) → Il en est sorti (“He left it.”)

French Reflexive Pronouns

A reflexive pronoun in French is an object pronoun that refers to the same thing as the subject of the sentence. They correspond to the English pronouns that end in “self”: “myself”, “yourself”, “himself” etc.

If you know how to say “my name is” in French, you’ve already seen a French reflexive pronoun. It’s the m’ in je m’appelle – literally, “I call myself”!

The French reflexive pronouns are:

| singular | 1st person (je) | me |

| 2nd person (tu) | te | |

| 3rd person (il/elle) | se | |

| plural | 1st person (nous) | nous |

| 2nd person (vous) | vous | |

| 3rd person (ils/elles) | se |

Note that the reflexive pronouns look identical to the direct object pronouns, except in the third person, where it’s se in both the singular and plural. Se abbreviates to s’ before a vowel sound.

- Je me regarde dans le miroir. – “I look at myself in the mirror.*

- On se connait? – “Do we know each other?”

- Il s’est lavé. – “He washed himself.”

- *Ils se sont lavés – “They washed themselves.”

- Nous nous amuserons. – “We’ll amuse ourselves.” Note the difference between reflexive and direct/indirect object pronouns:

- Ils se voient. – “They see each other.”

- Ils les voient. – “They see them” (i.e. they see someone other than themselves.)

- Elles se parlent. – “They’re talking to each other.”

- Elles leur parlent. – “They’re talking to them” (i.e. someone else.)

French Pronoun Order

When a phrase contains multiple personal pronouns, they follow a strict order:

| Number | Person | Slot | ||||||

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | ||

| Singular | 1st | je | ne | me | ||||

| 2nd | tu | te | ||||||

| 3rd | il | se | le | lui | y | en | ||

| elle | la | |||||||

| on | le/la | |||||||

| Plural | 1st | nous | nous | |||||

| 2nd | vous | vous | ||||||

| 3rd | ils | se | les | leur | y | en | ||

| elles | ||||||||

What this means is that, when constructing a verbal phrase, you can pick at most one pronoun from each column, and they must appear in your sentence in the same left-to-right order as the columns.

Additionally, columns 3 and 5 can’t coexist. So for example, se and lui can’t appear in the same phrase.

If your verb phrase would need multiple pronouns from the same column, or a pronoun from both columns 3 and 5, rephrase it with à or pour for the indirect object: Je me donne à toi (“I give myself to you.”)

If this all looks complicated, don’t worry. You don’t need to memorise this table from scratch. Just get a sense of the pronoun order from example sentences, and use the table as a reference if you need to double-check.

It won’t be long before you get a feel for the correct way, and anything that doesn’t follow the rules will sound wrong to you.

French Pronoun Order With Multiple Verbs

There are two situations in French where you use two verbs in a row.

Firstly, there are the compound tenses. These are verb tenses like the passé composé (past perfect) which use an auxiliary verb (avoir or être). In compound tenses, object pronouns go before the auxiliary verb:

- Elle l’a vu – “She saw it.”

- Ils lui auront donné le cadeau – “They’ll have given him the gift.”

- Je me suis levé tard – “I got up late.”

Then there are dual-verb constructions with verbs like aller (“go” or “will”), pouvoir (“can”), devoir (“must”), vouloir (“want”) and falloir (“must”).

In these constructions, object pronouns go between the two verbs:

- Il devrait le lire. – “He should read it.”

- Je voudrais en parler. – “I’d like to talk about it.”

- Il ne veut pas te voir. – “He doesn’t want to see you.”

- Je vais leur demander. – “I will ask them” or “I am going to ask them.”

French Stressed Pronouns

Stressed pronouns in French, otherwise known as disjunctive pronouns or emphatic pronouns, are strong forms of pronoun that can be used for emphasis, or when you need a pronoun to stand alone without being linked to a verb.

Think about these two English exchanges. Which one sounds correct?

- “Who won the race?” “Him!”

- “Who won the race?” “He!”

The answer (unless you are a strict, old-school grammarian) is that the first one sounds more correct.

How about these two phrases?

- “I, I’m just happy everything worked out.”

- “Me, I’m just happy everything worked out.”

The second one should definitely sound like the right one (even to the strict grammarians out there).

These examples are pretty close to how French stressed pronouns work as well.

The stressed pronouns are as follows:

| moi | me |

| toi | you |

| lui | him |

| elle | her |

| nous | us |

| vous | you |

| eux | them – masculine or mixed |

| elles | them – feminine |

When to Use Stressed Pronouns in French?

Use a stressed pronoun in the following circumstances:

- In so-called “cleft sentences”. These are redundant, emphatic sentences where you use multiple clauses to say something that could have been expressed by one clause. For example: c'est toi que j’aime – “it’s you that I like.”

- When you need to use more than one pronoun for the subject: Lui et moi sommes frères – “He and I are brothers”. (Equivalently, you could say Lui et moi, nous sommes frères.)

- When repeating a pronoun for emphasis: moi, je l’ai fait – “Me, I did it.*

- After que in comparisons: Il est plus riche que moi – “He’s richer than me.”

When using on to mean “we”, the stressed version is nous: Nous, on ne parle pas l’anglais.

Soi is a stressed pronoun that refers back to the existing subject of the sentence:

- Un voyageur sait se sentir chez soi n'importe où – “A traveller knows how to feel at home anywhere.”

Soi can also refer to a generic, unspecified person: Chacun pour soi! – “Every man for himself”.

French Possessive Pronouns

Possessive pronouns are for stating that something belongs to someone. In English, these would be words like “mine”, “yours”, “hers”, etc.

French possessive pronouns work the same way, with a couple of differences:

- The pronoun must match the gender and number (singular or plural) of the noun it replaces.

- A definite article – le, la or les – comes before the pronoun.

Here is a summary of all the possessive pronouns in French:

| Singular | Plural | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Masculine | Feminine | Masculine | Feminine | |

| mine | le mien | la mienne | les miens | les miennes |

| yours (tu) | le tien | la tienne | les tiens | les tiennes |

| his, hers, its | le sien | la sienne | les siens | les siennes |

| ours | le nôtre | la nôtre | les nôtres | les nôtres |

| yours (vous) | le vôtre | la vôtre | les vôtres | les vôtres |

| theirs | le leur | la leur | les leurs | les leurs |

And a couple of example sentences:

- Est-ce que ce portefeuille est le tien ? Oui, c’est le mien. (“Is this wallet yours?” “Yes, it’s mine.”)

- A qui sont ces assiettes ? Ce sont les nôtres. (“Whose plates are these?” “They are ours.”)

French Relative Pronouns

Relative pronouns in French are pronouns which introduce a relative clause. A relative clause is a clause which gives additional information about a noun.

Relative clauses are introduced in English by words like “who”, “that”, and “which”:

- “Have you seen the book that I was reading?”

- “You’re the one who told me that!”

The French relative pronouns are qui, que, dont, où, and lequel/laquelle/lesquels/lesquelles. Let’s examine them in turn.

The Relative Pronouns Qui and Que in French

Qui and que are the most basic relative pronouns in French. They link two clauses in the same way as the English words “that” or “which”.

The difference is that qui is used for the subject of the sentence, while que is used for the direct object:

- Le chien qui m’a mordu est noir. – “The dog that bit me is black”

- Le chien que j’ai adopté est un bouledogue. – “The dog that I adopted is a bulldog.”

In the first sentence, the dog is the subject of the verb mordre (“to bite”). That is, the dog is biting, not being bitten. Therefore, we use qui.

In the second sentence, the dog was adopted, it wasn’t adopting. So the dog is the object, and we use que.

Both of these words can be used for people as well as things. That is, there’s no reason they can’t be translated as “who” or “whom”:

- La personne qui l’a cassé n'est pas ici. – “The person who broke it is not here.”

- La dame que j’ai rencontrée hier était gentille – “The woman whom I met yesterday was nice.”

When que comes before a vowel sound, it’s abbreviated to qu’. Qui is never abbreviated.

- La maison qu’il a achetée est énorme – “The house that he bought is huge”

- Voici le livre qui était sur la table – “Here’s the book that was on the table.”

In English, it’s often possible to drop the relative pronoun altogether. For example, instead of saying “the dog that I adopted”, we can simply say “The dog I adopted”.

This is not possible in French – you can never leave the relative pronoun out.

The Relative Pronoun Dont in French

The relative pronoun dont sometimes seems more complicated to new French learners than it is. I promise it’s really straightforward. Simply put, you can nearly always translate this word into English as “of which (or whom)” or “about which (or whom)”.

The reason it can seem complicated is because in English, we don’t often use the terms “about which” or “of which” in everyday speech anymore. For example, the phrase “The dog about which I am speaking is white” sounds stuffy and formal. You’d probably rather say, “The dog that I am speaking about is white.”

So even though dont translates as “about which/whom” or “of which/whom”, those translated phrases themselves can be rephrased in English in a few ways. But don’t worry about that part, just remember that if it’s possible to say your English phrase using “of which/whom” or “about which/whom” – even if it would sound stuffy or formal – then the word you want to use in French is dont.

Here are some examples that cover most of the usages of dont:

- Il a un frère dont il est jaloux. – “He has a brother that he is jealous of.” (or: “He has a brother, of whom he is jealous.”)

- Elle a vu une araignée dont elle a eu peur. – “She saw a spider which she was afraid of.” (or: “She saw a spider, of which she was afraid.”)

- C’est le père de Pauline dont ils parlent. – “It’s Pauline’s father (that) they’re talking about.” (or: “It’s Pauline’s father about whom they are talking.”)

- J’ai acheté le crayon dont j’ai besoin. – “I bought the pencil that I need.” (or: “I bought the pencil of which I have need.”)

- Claude, dont la sœur est journaliste… – “Claude, whose sister is a journalist…” (or: “Claude, the sister of whom is a journalist…”)

- Je cherche une maison dont la porte est rouge. – “I’m looking for a house whose door is red (or: “I’m looking for a house, the door of which is red.”)

- Ceci est le sujet dont je vais écrire. – “This is the subject I’m going to write about.” (or: “This is the subject about which I’m going to write.”)

Two quick exceptions:

- La façon dont j’écris est spéciale. – “The way in which I write is special.” (In French, you do things of a certain way, not in a certain way, so you use dont here even though it translates as “in which”.)

- The phrase “The man about whom I’m writing an article…” would NOT translate into French as L’homme dont j’écris un article… In French, you write books/articles on a topic, not about it. So instead of dont here, you would use the relative pronoun in the next section:

The Relative Pronouns Lequel, Laquelle, Lesquels and Lesquelles in French

The relative pronoun lequel (and the feminine and plural versions laquelle, lesquels and lesquelles) work a lot like dont.

Basically, while dont translates as “of which/whom” or “about which/whom”, lequel can be used with all the other possible prepositions, such as “from which/whom”, “to which/whom”, “on which/whom”, “in which/whom”, “around which/whom”, “beside which/whom”… well, you get the idea.

(You’re less likely to use lequel when talking about a time or a physical location – more on that in the next section.)

This pronoun has four forms, to match the gender and number of the noun it replaces:

| Masc. | Fem. | |

|---|---|---|

| Singular | lequel | laquelle |

| Plural | lesquels | lesquelles |

These examples should cover most of the usages of lequel and its other forms:

- Voici le livre dans lequel je l’ai lu. – “Here’s the book in which I read it.”

- C'est la raison pour laquelle ce n’est pas possible. – “That’s the reason why it isn’t possible.” (or: “That’s the reason for which it isn’t possible.”)

- Voici la lettre à laquelle j’ai répondu. – “Here is the letter to which I replied.”

- L’homme à côté duquel je m’assis est mon mari. – “The man I’m sitting beside is my husband” (or: “The man beside whom I’m sitting is my husband.”)

- Les aliments auxquels je suis allergique sont les arachides et le lait. – “The foods I’m allergic to are peanuts and milk.” (or: “The foods to which I’m allergic are peanuts and milk.”) Note that auxquels is just the contraction of à lesquels – just like à + les has to be written aux in French, à + lesquels has to be written auxquels.

When the object is a person, you can (but don’t have to) use qui instead of lequel:

- Je suis l’homme sur lequel / sur qui le journaliste a écrit l’article. – “I’m the man whom the journalist wrote the article about.” (or: “I’m the man about whom the journalist wrote the article.”) Remember that in French, you don’t write an article about a topic, you write an article on a topic.

The Relative Pronoun Où in French

Finally, the relative pronoun où means “where” or “when”.

Où is used to replace nouns that refer to time…

- Je ne me souviens pas le jour où nous avons fait connaissance. – “I don’t remember the day when we met.”

- L’époque où il vivait était dangereuse – “The era he lived in was dangerous.” (literally: “The era where he lived was dangerous.”)

…or to replace nouns that refer to space or location:

- J’ai visité la maison où j'ai grandi – “I visited the house where I grew up.”

Où can be preceded by the prepositions de, jusque, or par, for example:

- Je me demande jusqu'où cela va aller. – “I’m wondering how far this will go.” (literally: “I’m wondering until where this will go.”)

- La direction d'où provient le signal – “The direction the signal comes from.” (literally: “The direction from where the signal comes.”)

- On ne sait pas par où il est allé – “We don’t know which way he went.”

French Demonstrative Pronouns and Determiners

The demonstrative pronouns in French are used to highlight, emphasise, or draw attention to something, or to distinguish one thing from another. They’re related to the demonstrative determiners (sometimes also called demonstrative adjectives.)

| Determiners | Pronouns | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| masculine | singular | ce (cet before a vowel sound) | celui |

| plural | ces | celle | |

| feminine | singular | cette | ceux |

| plural | ces | celles |

Use ce, cet, cette and ces to modify a noun. While English distinguishes between “this” and “that” for objects that are closer or farther away, French doesn’t make that distinction:

- Ces vêtements sont trop chers. – “These/those clothes are too expensive.”

- Cet acteur m’agace! – “This/that actor irritates me!”

Use celui, celle, ceux and celles to say “the one” or ”the ones”. You can use French demonstrative pronouns in three situations:

- With the suffixes -ci and -la. When paired with -ci, they mean “the one here” or “the ones here” – or, more naturally, “this one” or “these ones”. With -la, they mean “that one” or “those ones”. If using -ci and -la in the same sentence, then -ci comes first:

- Quel garçon l'a fait, celui-ci ou celui-là? – “Which boy did it, this one or that one?”

- Tu veux celles-ci? Non, je préfère celles-là – “Do you want these ones? No, I prefer these ones.”

- To introduce a clause with a relative pronoun. (Remember the relative pronouns?)

- Voici celle dont j’ai rêvé. – “Here is the one that I dreamt of.”

- Ce vin est celui que tu n’aimes pas – “This wine is the one you don’t like.”

- Ceux qui sont polis recevront un cadeau. – “Those who are polite will receive a gift.”

- With a prepositional phrase (usually one with de):

- C’est ta voiture? Non, c’est celle de mes parents.* – “Is this your car? No, it’s my parents’.”

Indefinite French Demonstrative Pronouns

The indefinite French demonstrative pronouns are ce (c’ before a vowel), ça, ceci and cela.

They refer to something abstract or unspecified, and, as such, they don’t need to agree with anything. This means they don’t have a number or gender.

Ce, when used as an indefinite demonstrative, means “this” or “it”. It’s usually used with être (“to be”):

- C’est important – “It’s important.”

- C’est la vie! – “That’s life!”

- Ce sont de bonnes nouvelles. – “It’s good news.”

Ce also works with devoir or pouvoir, but only when those verbs are followed by être.

- Ce doit être une mauvaise idée – “This must be a bad idea.”

- Ce peut être difficile de ne pas se fâcher – “It can be difficult not to get angry.”

Ce can also work without a verb, but it sounds pretty formal and isn’t very common:

- Elle a travaillé en Allemagne, et ce en tant que bénévole. – “She worked in Germany, and this as a volunteer.”

Use ça with all other verbs. This includes pouvoir and devoir when they’re not followed by être:

- Ça va? – “How are you?” (literally: “Does that go?”)

- Ça peut nous aider. – “It can help us”

Ça can also be used as the direct or indirect object of a verb:

- Je trouve ça très ennuyeux – “I find that very annoying.”

- Tu es d’accord avec ça? – “Do you agree with that?”

Ceci and cela mean “this” and “that” respectively. They can be used as drop-in replacements for ça, although they’re more formal, and less common in everyday speech:

- Je trouve ceci très ennuyeux – “I find this very boring.”

- Tu es d’accord avec cela? – “Do you agree with that?”

French Interrogative Pronouns

Interrogative pronouns in French are pronouns which are used to ask a question. There are four interrogative pronouns: qui, que, quoi, and lequel.

You may have noticed that qui and que are also relative pronouns, as we saw above. In that case, qui and que are used for the subject and object respectively of the relative clause.

But when they’re interrogative pronouns, the distinction is different.

The rule now that qui is used for people, while que is used for things. And both of them can be either the object or the subject of the sentence.

The Interrogative Pronoun Qui

Qui means “who” or “whom”, and is used to ask a question about people.

- Qui conduit? (“Who’s driving?”)

- Qui l’a fait? (“Who did it?”)

When qui is the object, you must invert the word order:

- Qui aimes-tu? – “Whom do you love?”

- Qui a-t-il vu? – “Whom did he see?”

Alternatively, you can use qui est-ce que:

- Qui est-ce que tu aimes? – “Who is it that you love?”

- Qui est-ce qu’il a vu? – “Who is it that he saw?”

Qui can be used with a preposition:

- À qui est-ce qu’elle parlait? – “Who was she talking to?”

- De qui est-ce qu’elle parlait? – “Who was she talking about?”

The Interrogative Pronouns Que and Quoi

The interrogative pronoun que means “what”. It’s used to ask a question about things, not people.

When que is the subject, use qu’est-ce qui:

- Qu'est-ce qui se passe? – “What’s happening?”

You can also use que with inverted word order and the addition of il, but this is uncommon:

- Que se passe-t-il? – “What’s happening?”

When que is the object, you can either invert the word order, or use qu’est-ce que:

- Qu’est-ce que tu manges? – “What are you eating?”

- Que manges-tu? – “What are you eating?”

Que after a preposition becomes quoi:

- De quoi est-ce que vous parlez? – “What are you talking about?” (Or: De quoi parlez-vous?)

Lequel As an Interrogative Pronoun

We already saw the four variants of lequel and how they can be used as relative pronouns. They also function as interrogative pronouns, in which case they mean “which one?” or “which ones”?

- Je vais acheter les chaussures. – “I’m going to buy the shoes.”

- Lesquelles? – “Which ones?”

Resources to Learn French

Whew! We’ve covered an enormous amount of ground.

Remember, this article is not meant to be binge-read and learned on the spot. You should just use it as a reference, something you can come back to when you need a reminder about a certain pronoun.

If you’re looking for tools and courses to make your French learning journey easier, you can try out some of the resources that I recommend here.

And the Fi3M has your back, of course! The French category covers all aspects of French from vocabulary to grammar to culture.

Bonne chance! (“Good luck!”)

Social