Why hard work isn’t what makes good learners

Why is that some people are worse language learners no matter how hard they work?

Among the many emails/tweets and in-person comments I get about those who have tried and failed to learn languages, what comes up more often than not is something along the lines of “I know that I can't ever learn French/German/Chinese because I lived in the country, studied for 8 hours a day, attended the best language school on earth, pirated got loaned the most expensive software and devoured it… and yet I don't speak the language!”

They list more and more things they attempted, as if the more things they say the more convinced I should be that they indeed are a special hopeless case. What I'm actually thinking each time they add something completely unrelated to the list, is If I was doing all that I'd probably get nowhere either!

I had the same misconception when I was learning Spanish for the first few months (where I got nowhere) that as long as I'm working hard I must be going in the right direction. This is flawed thinking, and I want to be an engineer again and use a comparison from vector theory!

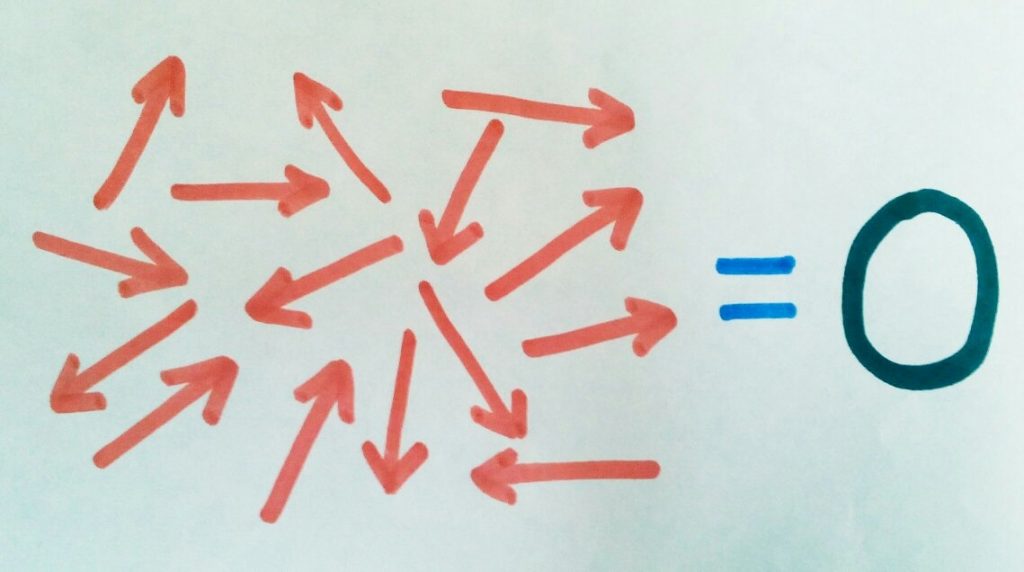

Hard work with no solid direction in mind

I found this image here about how hard work without discipline is like random vectors that cancel each other and result in a zero. This visual is exactly how I feel when I retrospectively look back on my first six months of Spanish, where I:

- Studied the dictionary from page one

- Took a class because it was expensive (and must be good)

- Tried to read El señor de los anillos (Lord of the Rings) with a dictionary

- Crammed (and forgot) verb conjugation tables

- Had complex news broadcasts on in the background, hoping I would learn it subconsciously and passively

- Decided every week that next week would be the one where I was finally “ready”, just after I've learned a few more basic words…

- Studied a word list I found somewhere, always from the top to the bottom

This is quite a list of things to keep me busy! I was working hard but after six months I was still barely able to ask the most basic questions. I was your stereotypical hopeless case.

The problem is that all of these tasks are unrelated, random and focus on extremely dissimilar problems. I was essentially trying to pull myself in so many directions, that they all cancelled one another out until I ended up effectively back at zero.

The thinking goes (for a work-hard-on-everything mentality) that you should be learning how to improve your conjugation, pronunciation, common and uncommon vocabulary, word genders, reading skills, writing skills, exam skills, spoken skills, and everything else that is involved in learning a new language, and you need to be doing it all NOW.

So if you find yourself trying lots and getting nowhere, think of this:

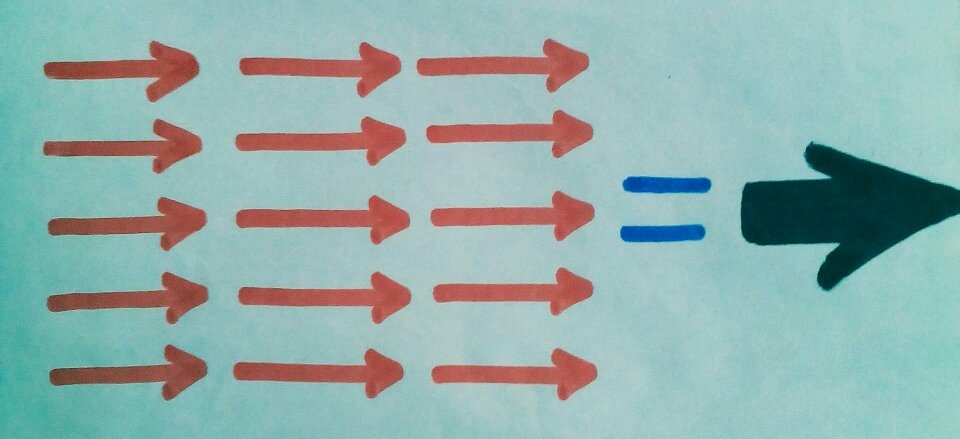

Deliberate practice: Work SMART, not hard

What changed for me was that I decided not to just randomly pull my Spanish in whatever direction I could imagine, hoping it would get generally better, but to focus on specific problems.

I know this can seem counterinterative, because as a beginner, you imagine that your ultimate end-goal is to master the language. So you should be learning everything from the start. But rather than know a little of this and a little of that, being a confident speaker first (my first priority always) gives you the confidence and flow in the language to be better at learning harder words, or being able to read, or whatever your next focus is.

I wasn't speaking Spanish in my first six months, so I decided to make speaking Spanish the approach. I went up to every Spaniard I could and used the dozen or so words I knew with them. When I ran into a problem there and felt there was a word I needed more than anything, I looked that word up so I could use it next time.

When I was slightly better, I found other issues that came up that were the priority, so I went and fixed them. One problem at a time. And one thing to focus on at a time.

Everything I put time into required me to ask the question will this help me speak more Spanish with someone I may meet today, rather than will this help improve my general Spanish a little bit.

Every tiny bit of effort I put in, made me that extra bit better. I wasn't working as hard because learning Spanish started to become more fun, with daily (and hourly) rewards. It didn't feel like hard work, but it was consistently smart work.

This “deliberate practice” meant that when I was good at speaking, I moved on to other things, and did indeed become good at writing, reading and everything else required to pass the C2 (Mastery) exam in Spanish.

But I consider it a series of “vectors” building on one another sequentially, rather than a mess of learning random unrelated aspects of the language, that got me to where I am today.

Social