Memory Palace: The Perfect Technique to Boost Your Vocabulary

Memory palace… Does it sound too “fairy-tale” to you? Well, it’s not a new Disneyland attraction, but an effective way to become fluent in a new language, faster.

In this post, I’d like to show you a proven language learning technique you can use to memorize and recall difficult new words and phrases: mnemonics.

I’ll explain why mnemonics work, but in a way that you may not have encountered before. I’ll tell you about Memory Palaces and how to construct one expressly for boosting fluency in your target language.

Table of contents

- What Is the Memory Palace Technique? Let’s Talk About This Specific Mnemonic

- The Scientific Case for Mnemonics

- If Mnemonics Work, Why Don’t More People Use Them?

- A Short History of the First Memory Palace

- How Does a Memory Palace Work?

- Create Your Memory Palace In 4 Easy Steps

- How to Use Your Memory Palace

- Enter Abraham Lincoln!

- Practical Tips for Using Your Memory Palace to Master a Foreign Language

- The Power of the Memory Palace for Language Learners

Plus I’ll explain how Abraham Lincoln can help you learn faster.

What Is the Memory Palace Technique? Let’s Talk About This Specific Mnemonic

A mnemonic is a learning device that helps you recall difficult information.

One of the most powerful types of mnemonics is the Memory Palace. You can use a Memory Palace to memorize hundreds of words and phrases from your language of choice at will.

If the term “Memory Palace,” isn’t right for you, many people use other terms, including:

- memory castle

- mind castle

- mind palace

- method of loci

I’ve even heard language learners who use memory techniques call this approach the “vocab journey.”

We’re not going to get hung up on the terminology, but I prefer the term Memory Palace because of how St. Augustine associated what we’ve learned with treasure.

And let’s face it:

There’s nothing most of us treasure more than being able to speak a language.

The Scientific Case for Mnemonics

In his book Learning German with Mnemonics, German teacher Peter Heinrich reports positive results amongst students who used mnemonics to learn and memorize German articles like der, die and das.

As he points out, articles can be difficult to learn because as phonemes, they have no particular meaning.

But if you associate images with words… That’s another story.

For example, a boxer would be associated with all words that take the masculine article der. The feminine article die would be associated with a skirt, and the neutral article das with fire.

With these images, students can make faster progress, because der Bus becomes a boxer pounding on a bus, die Flasche becomes a Coke bottle wearing a skirt and das Band becomes a ribbon covered in flames.

Heinrich found the retention rate of learners not using mnemonics was 47 percent, whereas students learning German verbs, adjectives and other points of grammar using mnemonics had an 82 percent retention rate.

In a now famous study on mnemonic techniques, Professor Richard C. Atkinson demonstrated the ineffectiveness of rote learning by writing words repeatedly. He concluded “Mnemonic strategies have therefore had particular success in the learning of a language.”

Memory techniques don’t apply only to languages that stem from English. James Heisig has helped many students learn Japanese using mnemonics by using an approach similar to Benny Lewis’s for how he learns new words.

If Mnemonics Work, Why Don’t More People Use Them?

A key reason more people don’t use mnemonics is because the books advocating this method of language learning are centered on the authors. They are filled with examples that come from the imagination of the writer rather than teaching the reader how to create their own.

Few books teach you how to come up with your associative-imagery to encode the words and phrases you learn into your memory. But it’s an easy technique that I will show you shortly.

On top of that, mnemonics are rarely taught in the context of language learning or a Memory Palace.

One reason why is that people think using these techniques only adds more work. When used inefficiently, they will. But when used well and with the tips we’ll be covering today, they not only reduce the amount of work needed to learn, but also save you time and create more enthusiasm.

If they were only dreadful hard work, they would not have stood the test of time.

A Short History of the First Memory Palace

Sometime during 556-468 BC, the Greek poet Simonides of Ceos attended a banquet to give a speech. Someone called him outside, and at that moment the roof caved in and crushed everyone left in the building.

Because Simonides used a special memory technique to hold the names of all the attendees and where they had been sitting, he was able to identify all the bodies. Simonides’ achievement helped the bereaved families properly bury their dead.

And with this heroic act of memory, the idea of using a building or Memory Palace to place, store and retrieve information appeared in the western world.

But as memory expert Lynne Kelly has shown in her book, The Memory Code, Aborigines and many other prehistoric cultures used these techniques long before the Greeks discovered them.

Mnemonics truly are part of humanity’s history, and there is no sign of them stopping.

How Does a Memory Palace Work?

A Memory Palace is an imaginary construct in your mind that’s based on a real location. If you can see your bedroom in your mind, then you can build a Memory Palace.

Within your Memory Palace, “stations” are locations like a bedroom or sitting room and the space between them is called a “journey”. As you build your Memory Palace, you will leave words and phrases at these stations and then pick them up later on when you take a journey through your palace.

Please don’t rob yourself of this powerful language learning device by saying you’re not a visual person.

In whatever way feels natural, just think about where your bedroom is in relation to your kitchen. Consider how you would move from the bedroom to the kitchen. Take note of the doors, hallways and rooms along the way.

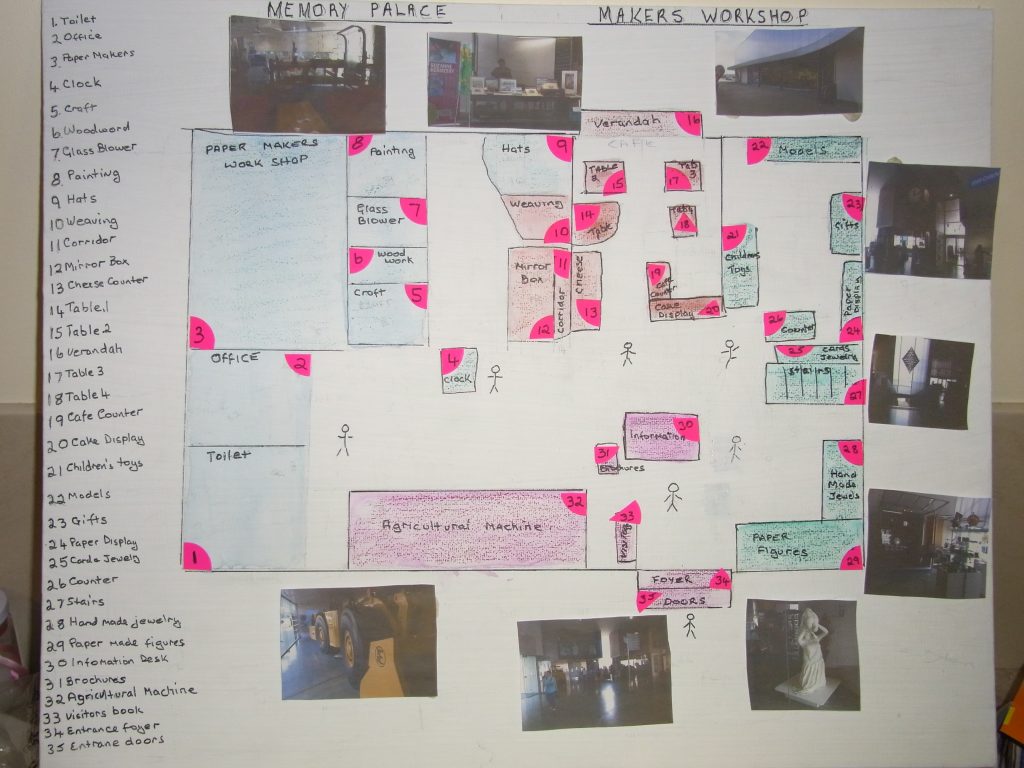

As an example, this image is a simple drawing of a high school I attended:

Each station in this Memory Palace has a number. These numbers are for creating a top-down or numbered list of the stations in the Memory Palace.

Create Your Memory Palace In 4 Easy Steps

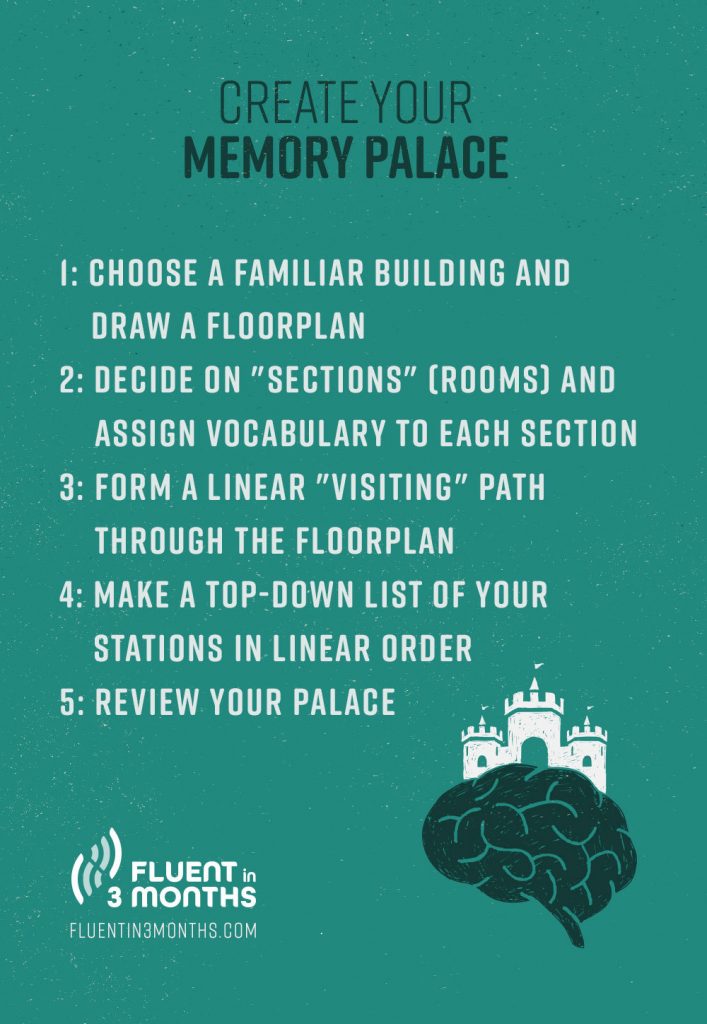

Step 1: Choose a familiar building and draw a floorplan.

This can be your home, a school, church or movie theatre. It can be any building so long as you know it well enough to draw a floor plan.

Step 2: Form a linear path through the floorplan.

Do this before you number your stations. Memory Palaces work best when you don’t cross your own path or lead yourself into a dead end.

Don’t cram every possible station into your first palace. Include the obvious locations like a bathroom, bedroom, living room, kitchen, as well as an entry point.

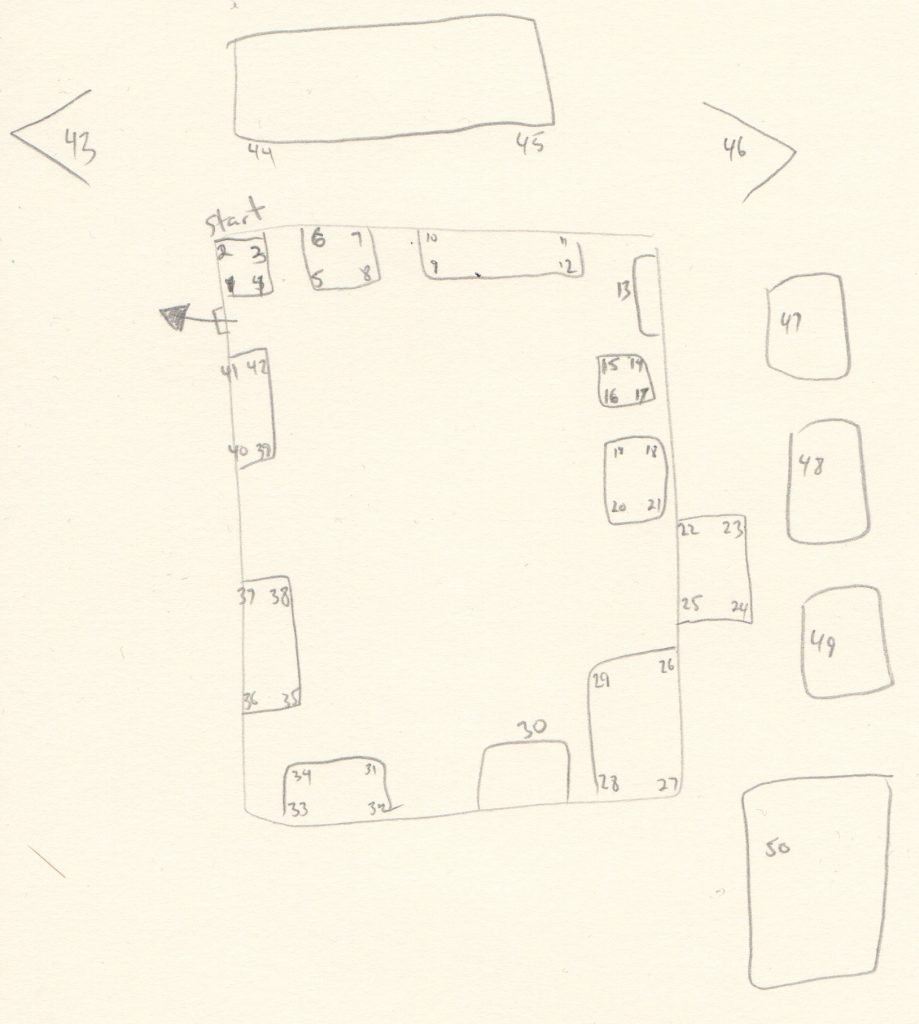

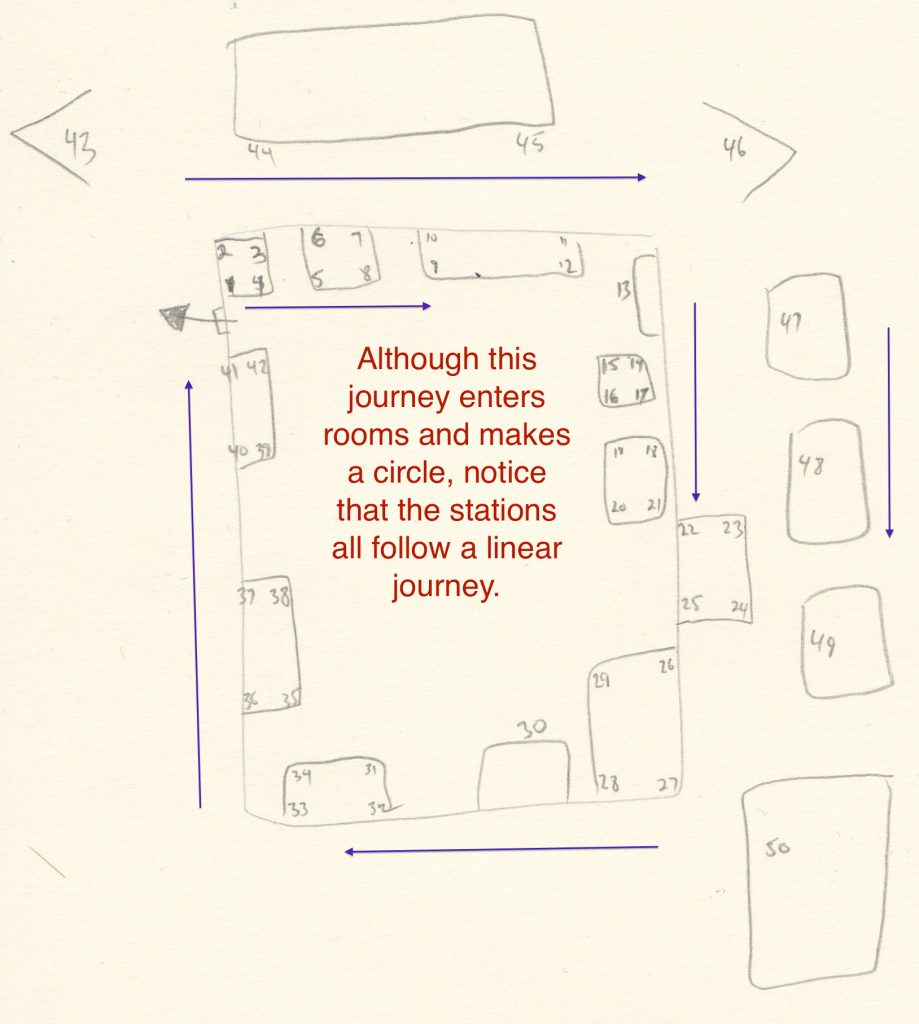

Here’s an example of the same Memory Palace with arrows:

Notice that my journey is simple and linear. Because I know this location well, it is almost nothing for me to think about as I move from station to station.

You should select buildings with which you have a similar level of familiarity.

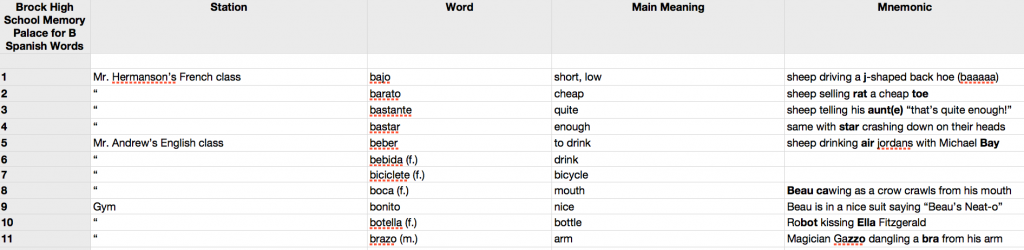

Step 3: Make a top-down list of those stations in linear order.

This step is useful for testing purposes. Here’s an example of how you can create such a document:

Step 4: Review your palace.

At this point, you should have:

- a floorplan of a familiar building

- a linear path drawn on the floorplan that does not cross itself

- designated a starting point and exit point

- numbered the stations

- written the top-down list

- walked through the Memory Palace (floorplan) several times so you can see or recall each station.

Congratulations on constructing your first Memory Palace!

How to Use Your Memory Palace

Now, it’s time to learn how to place words and phrases on each of the stations in your Memory Palace.

To make these words and stations memorable, we’re going to use the three classic principles of learning and memory. These are:

- Paying attention in a special way to target words and phrases.

- Encoding the sound and meaning of information using imagery and action so each word or phrase becomes memorable.

- Decoding imagery and actions so you can move words and phrases into long-term memory.

To encode your information, create images that are large, bright, colorful, weird and filled with intense action. You can stick the images to a station in your Memory Palace and revisit them at any time.

Tip: exaggerate this imagery so that you can retrieve them by drawing on sounds and meaning.

For example: If you’re learning Spanish and you discover that “tengo para dar y regalar” basically translates in English to, “I’ve got plenty to share,” would you find that phrase immediately memorable?

Probably not.

But what if I told you I’d seen a strange performance of a tango dance with Darth Vader tangled up in a parachute? And, in his frustration, he’s trilling an “r” with his tongue through his breathing grill while trying to share an egg with his dancing partner. She herself is a giant egg and also tangled up with Darth Vader in the parachute. She says, “no thanks, I’ve got plenty.” Darth Vader responds, “No really, I’ve got plenty to share.”

Are you able to see that scene in your mind? It’s such an unusual image that chances are you can.

Next, imagine this scene taking place in your bathtub. Really concentrate on the elements. This is the kind of outlandish image and sound-based story you need when you bring your mind back to your bathroom tub and decode it.

The equation here is:

Tango + para(chute) + Dar(th Vader) trilling “r” and handing off a r”egg”ular = “tengo para dar y regalar”.

With a few visits to the story and practice decoding it for sound and meaning, followed by use in a speaking session, the phrase will quickly pour itself into long term memory.

Notice how, in this example, I’ve tied sound to meaning using the images and actions. It’s not just that Darth Vader trilling his “r” and handing off an egg helps recall the sound of the word. The action also helps regularize the meaning of the word in the context of the phrase.

Your Memory Will Improve

Obviously, this example doesn’t provide a one-to-one correspondence. I also haven’t incorporated “y,” but if I needed to, it would be as simple as having Darth Vader wearing a “y” shaped neck brace that shouts “eee” at the situation. But in general, small words like “y” tend to take care of themselves if you let them.

As the memory champion Ben Pridmore once said in an interview, if you’re willing to trust your memory after training it with these techniques, you’ll be pleasantly surprised by how well it performs.

If you create similar scenes and images on your own, they’ll be close enough to jog your memory. The more you practice, the better you’ll get.

And remember, these are mnemonic examples from my mind. In order for these procedures to work for you, you have to come up with your own images and actions.

The reason this story works for me is because I’m a fan of Star Wars, I love tango music and it’s just the image that my imagination brought to me.

The important principle to notice here is that the more you draw upon information that already exists in your memory, the less work you have to do to get new information in. And if you let yourself relax and your imagination flow, you’ll find that with a minimum amount of practice, you can create memorable and useful images like these too.

Enter Abraham Lincoln!

We can take things further and make the combination of a Memory Palace station like a bathtub much more useful using another technique: a bridging figure.

The concept of a bridging figure will help you supercharge your Memory Palace and accelerate your learning. This figure is someone who takes an imaginary journey through your Palace and interacts with your images for each word.

Ideally, your bridging figure should be a person you already remember.

For example, I use Abraham Lincoln for words that start with “A.”

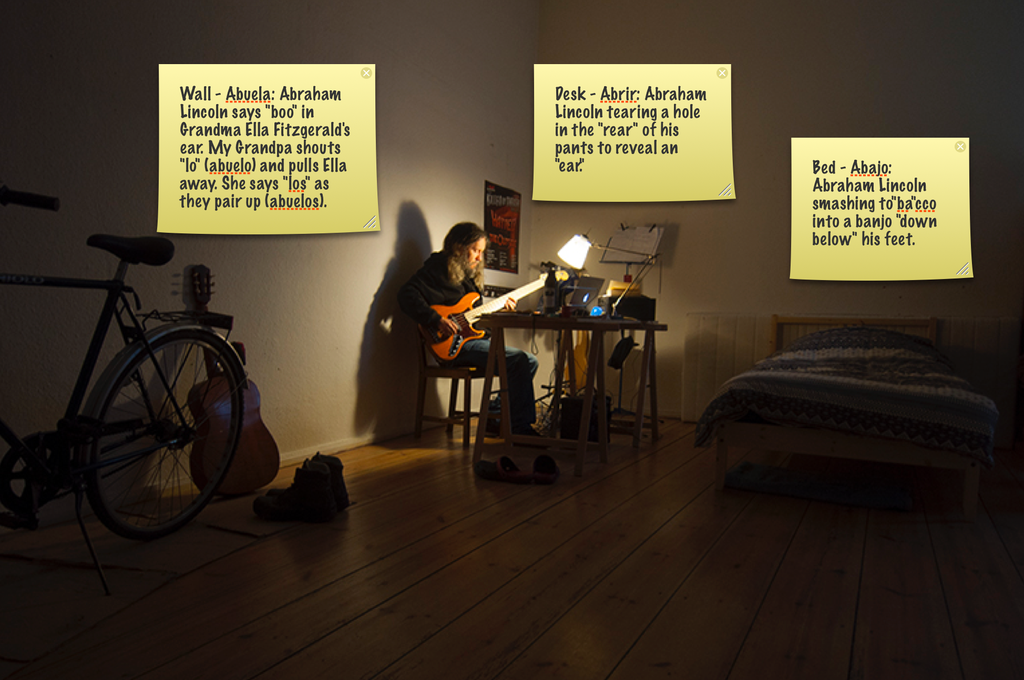

In this example, you can see Abraham Lincoln assisting me with the memorization of four Spanish words using a journey in my old office in Berlin.

Bed – Abajo: Abraham Lincoln smashing to”ba”cco into a banjo “down below” his feet.

Desk – Abrir: Abraham Lincoln tearing a hole in the “rear” of his pants to reveal an “ear.”

Wall – Abuela: Abraham Lincoln says “boo” in Grandma Ella Fitzgerald’s ear. My Grandpa shouts “lo” (abuelo) and pulls Ella away. She says ,”los” as they pair up (abuelos).

I recommend focusing only on the words that interest you the most and that you think you’ll use.

In other words, you don’t have to memorize an entire dictionary like Dr. Yip to get great results by reaching your vocabulary building goals.

Practical Tips for Using Your Memory Palace to Master a Foreign Language

- Build a well-constructed Memory Palace using the principles you’ve just learned.

- Relax. Memory techniques work best when you’re mentally and physically free from stress.

- Memorize a selected list of words, ideally in alphabetic order.

- Catalog the words, meanings and mnemonics either by hand on paper or in an Excel file or the equivalent.

- Remove yourself from your written record or Excel file and all other materials that might cause you to cheat by looking up the meanings of each word.

- Write out the words and meanings based on your memory on a piece of paper. Don’t worry if you miss a word or your associative imagery fails to trigger the sound and meaning of a word on your list. You can fix this later.

- Check the list you produced from memory with your record.

- Use these words in conversations, write them into a ten-sentence email and keep your eyes and ears open for them as you read and listen to your target language.

The Power of the Memory Palace for Language Learners

Related Learning: The Best Way to Learn a Language (Scientifically Proven, Polyglot Tested)

A Memory Palace is a powerful language learning device that you can use alongside other techniques to learn and speak a foreign language.

Constructing a Memory Palace takes just a few hours and as you become more proficient building them, this method of learning will help you grow your vocabulary faster.

Once you have stored words and phrases in your Memory Palace, draw on them often as part of your speaking practice. You may stumble and pause while accessing these words and phrases, but don’t worry: this is something we do in our mother tongues too.

If you practice and relax, the words and images you’ve created in your Memory Palace will come back to you when you need them, and they’ll make the process of learning and speaking a foreign language feel easier and more enjoyable.

So if you’re ready and excited to build a Memory Palace and start using it to stock up on words and phrases, you can tap your mind for familiar locations starting right now. Happy memorizing!

If you want more help constructing a memory palace, you can check out the Magnetic Memory Toolkit – it’s free!

Original article by Anthony Metivier, updated by the Fluent in 3 Months team.

Social