Sentence Structure: How to Build Sentences and Use the Correct Word Order in Any Language

Sentence structure can be analysed in several ways.

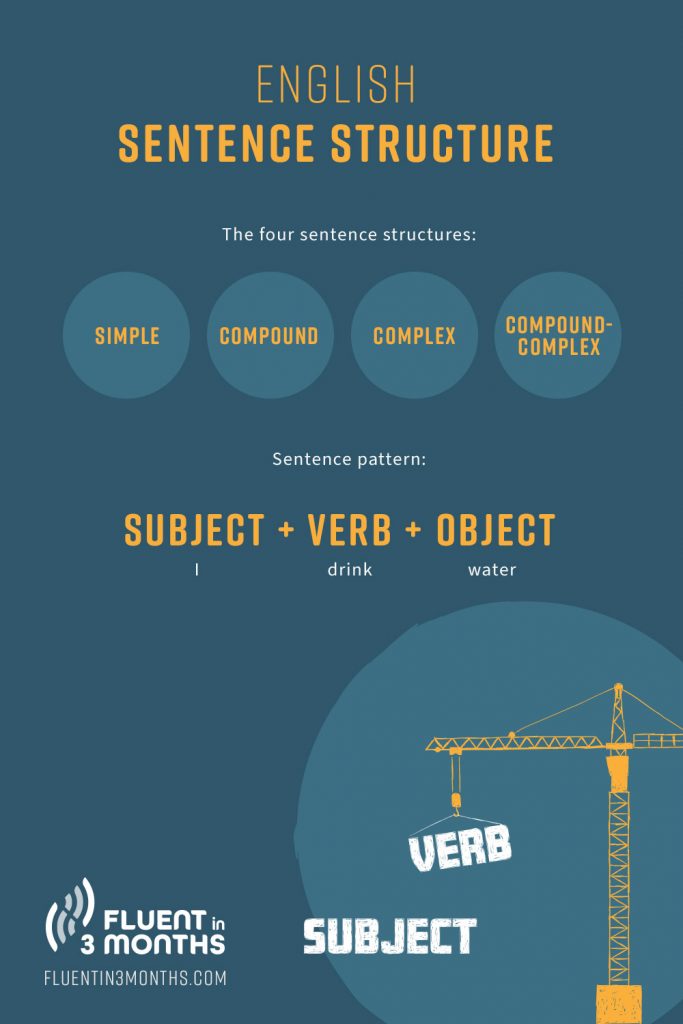

If you’re thinking about sentence structure in English, your first reflex might be to analyse how many independent and dependent clauses a sentence has.

- Independent clauses are groups of words (with a verb) that can work as full sentences on their own → “We have to eat.”

- Dependent clauses are groups of words (with a subject and a verb) that only make sense with independent clauses → “We have to eat before the food gets cold.”

Depending on the number of independent and dependent clauses they contain, sentences can be simple (1 independent), compound (2+ independent), complex (1 independent + 1 dependent), or compound-complex (2+ independent + 1+ dependent).

But language learners tend to focus on another aspect of sentence structure first: the order of elements in the sentence.

“What's the best way to learn difficult sentence structure and word order?”

This is a question me and my team get asked a lot here at Fluent in 3 Months (Fi3M). No matter which language you're learning, sentence structure is a common stumbling block.

Thankfully, there are some general principles that can help you learn sentence structure in any language.

Here’s what we’ll cover in this post:

Table of contents

- What Is Sentence Structure

- The Old-and-Broken Rules for Learning Sentence Structure

- Why Learning Sentence Structure Rules Doesn't Work

- In Your Native Language, You Know Sentence Structure by Instinct

- How Your Brain Learns Grammar

- How to Use Your Brain’s Toolkit to Learn Sentence Structure

- Test Yourself: Learn Sentence Structure by Creating Sentences

What Is Sentence Structure

Sentences are made up of a few basic elements. As a simple definition, and in this instance, sentence structure is the order in which these elements are used to compose a grammatically correct sentence.

When dealing with basic sentence structure, you only need to acknowledge three components:

- subject

- predicate (verb or verb phrase)

- direct/indirect object

In English, these elements follow a specific order to form sentences: SVO. This acronym stands for “subject, verb, object”.

Think about it: it’s natural to say “I drink water”. You can’t say “Water I drink” (unless you’re Master Yoda).

In romance languages such as Italian, Spanish, and French, the sentence pattern is the same as in English: subject, verb, object.

In contrast, basic Korean sentence structure and basic Japanese sentence structure place the subject first, followed by the object, and finish with the verb. While in English we say “I drink water”, Korean and Japanese sentence structure would have it, “I water drink”.

Russian sentence structure is much more flexible. Commonly, it uses the subject-verb-object structure, the same one English uses. However, virtually all combinations of subject, verb, and object are valid in Russian.

The Old-and-Broken Rules for Learning Sentence Structure

The textbook approach to sentence structure is “learn a big long list of boring rules.”

For example, here are some German sentence structure rules that a teacher might have you memorise:

- Basic word order is subject, verb, object, like in English. “I drink water” = Ich trinke Wasser.

- When there's a modal verb like “want to”, “try to”, etc., the other verb gets moved to the end. “I want to drink water” = Ich will Wasser trinken.

- In “subordinate clauses”, the verb also gets shunted to end. So “I drink water” is Ich trinke Wasser but “I think that I drink water” is Ich denke, dass ich Wasser trinke. Note how “trinke” gets moved to the end.

That's just a small sample of how this approach might work in German. The list goes on: What if there are two modal verbs? What if a subordinate clause has modal verbs? What if the modal verbs are in a different tense? What if there are multiple subordinate clauses?

With enough patience, you'll remember all the rules for all of these cases… maybe.

And of course there are different rules for Spanish sentence structure, French sentence structure, Italian sentence structure, and so on. Do you really want to study a new rulebook for every language?

Why Learning Sentence Structure Rules Doesn't Work

There are two problems with sentence structure rules.

First, language is infinite. No matter how many sentence structure rules you learn, there will always be a longer, more complicated sentence that leaves you stumped.

Second, learning rules is boring, inefficient, and, most importantly, unnecessary. You've already learned at least one language without consciously studying the rules of its sentence structure. You might not believe this, but you can do it again.

To understand how, let’s take a more detailed look at how you learned sentence structure in your native language.

In Your Native Language, You Know Sentence Structure by Instinct

You probably can't even explain what all the rules of your native language are, but you know when the rules are being broken. Let’s use an example to illustrate that:

Imagine that a German friend says to you “I went yesterday by train to the city” (This is a common mistake that German speakers make in English, for reasons that we'll see.)

If you're a native English speaker, that sentence will have set off alarm bells in your head.

How do you know there's a mistake?

A linguist could tell you that English sentences typically follow the structure place-manner-time. German uses time-manner-place, which is where your friend's mistake came from.

You don't need the technical explanation though. The sentence “I went yesterday by train to the city” just feels wrong, and you know it instantly.

How Your Brain Learns Grammar

The human brain learns grammar through pattern recognition.

Somewhere in your head is a database of “correct” English sentences that you've been building up since infancy. When a new sentence comes in, your brain performs a quick check to see if it “fits” the patterns it's used to. If it does, all good. If not, it triggers an uncomfortable discord.

This is the linguistic equivalent of hearing someone sing out of tune.

If you're a native English speaker, this is how you learned English sentence structure as a child. No one ever explained the “place-manner-time” thing to you. You might have never even thought about it until you read this article. Your brain just figured it out by listening to lots and lots of English.

This isn't like learning to do long division. It's programmed deeply into our brains by over 100,000 years of evolution. Humans learn grammar like bats “learn” to navigate by echolocation. It's part of our natural toolkit.

How to Use Your Brain’s Toolkit to Learn Sentence Structure

How can you take advantage of your brain’s programming as an adult?

It's simple: stop focussing on the why of sentence structure, and start focussing on the what.

It's not that you should never study the rules. Rules can still be helpful, but I suggest you leave them till later. Start by listening to and reading your target language as much as possible. Your brain will get to work behind the scenes figuring out the patterns.

The content you're taking in should always be a tiny smidgen outside your current level of understanding. If you understand it all perfectly, there's nothing for you to learn. If you don't understand any of it, you won't learn anything either.

With enough of this input, eventually you'll be able to feel the correct grammar, in the same way you just feel that it's wrong when someone says “I went yesterday to school.”

After you're comfortable with this, it's time to go back to the grammar books and consult the rules. This will help cement what you've learned, and clean up any lingering mistakes in your understanding.

In other words, rules are a terrible way to learn a language from scratch. But they are useful to polish up what you already know.

Test Yourself: Learn Sentence Structure by Creating Sentences

Reading and listening are good ways to learn sentence structure, but they're passive activities.

You'll learn much faster if you turn it into something active, forcing your brain to create sentences rather than just take them in. A good way to do this is to turn your input into a test.

Whatever grammatical concept you're trying to learn, I recommend you find (or create) a big list of example sentences that illustrate the concept. For example, say you're learning German and you want to remember how the word order works for modal verbs.

Find the page in your grammar book that explains this point. If the book is anyway decent, it will give some examples of sentences that contain modal verbs, such as ich will Wasser trinken.

Assimil, Glossika and LingQ are all useful tools here, as they teach through exposure to full sentences rather than through explaining grammar. They're a great place to find example sentences.

Once you’ve got example sentences, I recommend turning them into flashcards using Anki. For each sentence, break it up into chunks and create a “question” flashcard that asks you how to reconstruct the broken sentence with the correct structure.

Here’s an example card for the sentence ich will Wasser trinken:

Where does the word “trinken” go in this sentence? ich will … Wasser …

Then the other side of the card should simply show the full sentence:

ich will Wasser trinken.

(You could also include a picture of someone drinking water, just to hammer the point home.)

Now, your job is to review the flashcards regularly until you can remember the answers to all of your questions. Look at a card, make a guess, flip it over, and see if you got the answer right. If you did, congratulate yourself. If not, try and remember it next time.

With a few different example sentences, it won't take long for the rule to be burned into your head.

If you find that you keep getting it wrong and you don't understand what the problem is, NOW it's a good time to go back to your grammar book and read the technical explanation.

Or if you feel like you’ve dealt with too much serious grammar today, check out Benny Lewis’ post on learning grammar through games.

Social