How to Learn the Vietnamese Alphabet: An In-Depth Guide

If you've just started learning Vietnamese, then the alphabet can look a bit challenging. Sure, it's based on the same Latin alphabet that we use in English, but it has some additions, like đ and ơ.

What’s more, the written language is covered all over with diacritics (accent marks). You'll often see multiple accents per word, or even per letter. It can be difficult for your mind to process if you’re not used to it, and it's far from obvious how to pronounce words like đở, một, or người.

But don't get too discouraged. The Vietnamese alphabet might seem tricky, but it's still far easier than learning a completely new writing system like that of Thai, Japanese, or Korean. If you're familiar with the Latin alphabet then you're already 90% of the way to being able to read Vietnamese. And I promise, the remaining 10% is not as difficult as you may think.

In this article I'll explain why that's the case, and teach you everything you need to know to start reading Vietnamese with ease.

The Vietnamese Alphabet: A Historical Introduction

Vietnamese used to be written using a pictorial system called chữ nôm that's similar to modern Chinese characters. These days, chữ nôm is all but dead. Modern Vietnamese uses a Latin-based alphabet called chữ Quốc ngữ (“national language script”) which was originally devised by Portuguese and Italian missionaries in the 16th century.

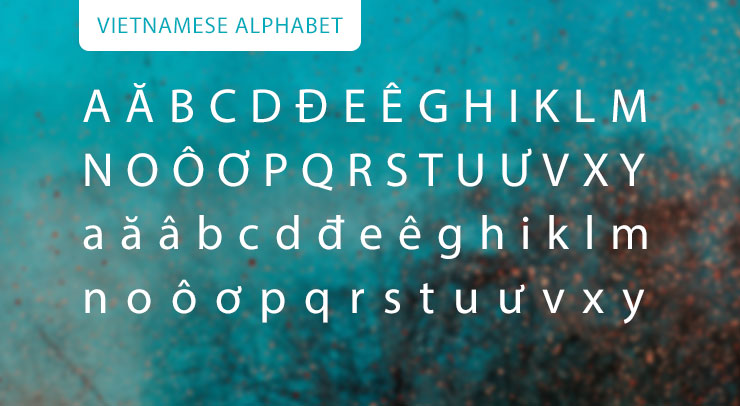

Chữ Quốc ngữ has 29 letters and here's what they look like:

(Note that Vietnamese doesn't use the Latin letters F, J, W, or Z)

This might look complicated, but there's good news: Vietnamese spelling, unlike English spelling, is highly consistent and unambiguous. Once you learn the rules, it's relatively easy to figure out how a written Vietnamese word should be pronounced. And how a spoken word is spelled.

Before I explain what those pronunciation rules are, I want to address the number one question that new learners of Vietnamese always ask:

Why Do Some Vietnamese Letters Have Two Accents?

A very distinctive feature of Vietnamese writing is that some letters are written with two accents — like the “ế” in the word tiếng (“language”).

In my experience, this is such a major point of confusion for beginners that it's worth addressing before we go any further. If I don't clear things up now, it will be harder to explain later.

The problem goes back to those missionaries who wanted to write Vietnamese using the Latin alphabet. That alphabet only has five symbols for vowels – a, e, i, o, and u – which isn't nearly enough to cover all the different vowel sounds of Vietnamese.

They could have used the same symbol to represent multiple sounds, as is common in English. (E.g. “a” is pronounced differently in the English words mat, mate, and car.) Or they could have invented some entirely new symbols that look nothing like a, e, i, o and u.

Instead, they decided to add six new letters: ă, â, ê, ô, ư, ơ.

These new symbols should not be thought of as “a with a hat” or “u with a hook/tail”. In Vietnamese they're considered to be completely separate letters from the five “normal” Latin vowels.

They're listed separately in the dictionary, have their own names, and are pronounced differently. For example, e is pronounced like the “e” in the English “get”, and ê is (roughly) like the “ay” in “hay”.

So that explains the “hats” on ă/â/ê/ô, and the hook thing (technically called a “horn”) on ơ/ư. You'll never see those symbols on any letters apart from the ones I just mentioned, so you'll never see an “i” with a hat or an “a” with a horn.

You'll also never see these three diacritics in combination with each other. So, for example, no Vietnamese letter has both a circumflex (ˆ) and a breve (˘).

When would you put two accents on one letter? Before we can finish this long explanation, I need to explain another essential aspect of Vietnamese speaking and writing:

How to Read and Write Vietnamese Tones

Vietnamese is a tonal language. By changing the pitch of your voice, you can completely change the meaning of a word.

For example, ba, said with a flat tone, means “three”. Pronounce it with a rising tone, as if you were asking a question in English, and it means “governor”. Pronounce it with a low, throaty tone and it means “randomly”.

Tones are hard for a native English speaker to master. A full explanation of how to pronounce them is beyond the scope of this article. For now, you need to know that Vietnamese has six different tones. Try watching this short video for a quick introduction to how they sound.

In many tonal languages (e.g. Chinese), the writing system doesn't provide much information about which tone to use for a given word. Or the tone might be encoded in the written word, but the rules for figuring it out are very tricky and convoluted (as in Thai).

Here's the good news: reading Vietnamese tones is very easy. This is because the tone is clearly denoted using one of five accent marks. There are five such symbols for the six tones, because the “flat” tone is denoted by having no accent mark. Four of the tone symbols are written above the vowel, and one is written below.

In full, the six tones and their symbols are:

| Tone name | symbol | example word |

|---|---|---|

| ngang (“level”) | (none) | ma (“ghost”) |

| sắc (“deep”) | ´ | má (“mother”) |

| huyền (“sharp”) | ` | mà (“which”) |

| nặng (“heavy”) | ̣ | mạ (“rice seedling”) |

| hỏi (“asking”) | ̉ | mả (“tomb”) |

| ngã (“tumbling”) | ˜ | mã (“horse”) |

Again, I can't precisely explain in writing how the six different tones are pronounced. For now, just understand that they are pronounced differently.

Also note that in southern Vietnam, the “tumbling” tone isn't used. Southerners pronounce mã the same as mả, although they're still written differently.

So take the letter e, which as I've already explained is pronounced like in the English “get” or “bet”. Depending on the tone, this could be written e, é, è, ẻ, ẽ, or ẹ.

A syllable can't have more than one tone, so you'll never see two tone marks on the same letter. E.g. the hổi and ngã symbols ( ̉ and ~) would never be used together.

However, you can add a tone symbol to an “accented letter” like ă, ê, or ư. This is the only occasion on which a Vietnamese letter can have more than one accent. So ế, ỗ, ợ, and ữ are all valid, to give just a few examples.

Note that tone marks are only written on vowels. You'll never see ´ or ~ written above a consonant. But note that “y” is considered a vowel in Vietnamese, so ý, ỳ, ỷ, and ỹ are valid combinations.

So, in summary: there are two types of “accent marks” in Vietnamese. First, there are the accents on ă, â, ê, ô, and ư, which tell you that you're dealing with a different vowel from the equivalent with no accent. Second, there are the tone marks: é, è, ẻ, ẽ, ẹ, which can appear on any vowel, including the six vowels which already have some kind of accent mark. A vowel can have one accent from each category, as in ể or ộ – and this is the only circumstance in which a Vietnamese letter can have more than one accent mark.

Hopefully this long explanation has made things crystal-clear. That's the last thing I'll say about Vietnamese tones, or the accents used to write them.

Now it's finally time to explain how the individual letters of the Vietnamese alphabet are pronounced.

How to Pronounce Vietnamese Letters

There are a few things to understand before explaining how each Vietnamese letter is pronounced:

Firstly, some letters are pronounced very differently in northern Vietnam compared to in the south. Where differences exist, I'll explain both pronunciations.

Secondly, the pronunciation of some consonants changes depending on whether they're at the beginning of the end of the word. Again, I'll do my best to explain this in the table below.

Also: you know how the combinations “th”, “sh”, and “ch” have special pronunciations in English? That is, a “th” is not simply the combination of a “t” and an “h”, but its own separate sound. The same thing exists in Vietnamese; certain combinations of letters have their own pronunciations, which will also be given below.

Finally, a word of warning. Vietnamese is not an easy language for English speakers to pronounce. Several of its vowels and consonants have no equivalent in English, and it can take a lot of practice to get them right and have native speakers understand you.

There's only so much I can explain in writing; make sure to listen to recordings of each, get help from native speakers when possible, and above all, keep practicing. You'll get there eventually.

The following is a rough guide to the pronunciation of every Vietnamese letter, or combination of letters. I include the IPA symbol for each letter – if you don't know what IPA is or how to read it, see my previous article on the topic.

| Letter | IPA | Description |

|---|---|---|

| A a | /a/ | Like the “a” in “cat” |

| Ă ă | /ă/ | Like “a”, but shorter |

| Â â | /ə̆/ | Like the “ir” in “bird” or “work”, but shorter |

| B b | /ɓ/ | An “implosive b” sound. (See below for more about implosives.) |

| C c | /k/ | Like an English “k” |

| D d | /z/ (northern), /j/ (southern) | Like a “z” in northern Vietnamese, and a “y” in Southern Vietnamese. Make sure not to pronounce this like an English “d” – this is a common mistake among beginners! |

| Đ đ | /ɗ/ | An “implosive d” sound. (See below for more about implosives.) |

| E e | /ɛ/ | Like the “e” in the English “get” or “bet” |

| Ê ê | /e/ | Like the “ay” in the English “say”, but not diphthongised (see below) |

| G g | /ɣ/ | Like a “softer” English “g”. Identical to the “g” in Spanish words like hago. Sometimes written “gh”; see below |

| Gi gi | /z/ (northern), /j/ (southern) | Like a “z” in northern Vietnamese, and a “y” in Southern Vietnamese. Note that this is exactly the same as a Vietnamese “d” |

| H h | /h/ | Same as the English “h” |

| I i | /i/ | Like the “ee” in the English “bee” |

| K k | /k/ | Same as a Vietnamese “c”, i.e. an English “k”. See note below about when to write “c” and when to write “k” |

| Kh kh | /x/ | A raspy “h” sound, like the “ch” in the Scottish “loch” |

| L l | /l/ | Same as the English “l” |

| M m | /m/ | Same as the English “m” |

| N n | /n/ | At the beginning of the word, this is pronounced the same as the English “n”. At the end of the word, northerners pronounce this like an “n”, and southerners like an “ng” |

| Ng ng | /ŋ/ | Like the English “ng”, as in “sing”. The difference is that, in English, the “ng” sound only ever comes at the *end* of a syllable. In Vietnamese it can also appear at the beginning of a syllable/word. Sometimes spelled “ngh”; see below |

| Nh nh | /ɲ/ (beginning of word), /ŋ/ (end of worth, northern), or /n/ (end of word, southern) | At the beginning of a word, this is pronounced like a “ny”, or the Spanish “ñ”. At the end of a word, it's pronounced like an “ng” in the North, and an “n” in the South |

| O o | /ɔ/ | To Brits, Aussies, and New Zealanders, this is like the “o” in “hot”. To Americans, it's more like the “ou” in “thought” |

| Ô ô | /o/ | Like the “ow” in “below”, except not diphthongised (see below) |

| Ơ ơ | /ə/ | To my British ear, this sounds exactly like the “ir” in “bird” or the “ur” in “fur” |

| P p | /p/ | Like an English “p”. Only ever occurs at the end of a word, except in “ph” which has a different pronunciation (see below) |

| Ph ph | /f/ | Like the English “f”. Only ever seen at the beginning of a word |

| Qu qu | /kʷ/ | Like the “qu” in English, e.g. “queen” |

| R r | /z/ (northern), /r/ (southern) | In the north, like “z”, or like the “s” in “vision”. In the south, a “tapped r”, as found in Spanish or Portuguese, and like the “tt” in the American pronunciation of “butter” |

| S s | /ʃ/ or /s/ | Like the English “s”. In the North, often pronounced like an English “sh”. |

| T t | /t/ | Like an English “t” (almost – see below). In the south, often pronunced as a “k” at the end of a word. |

| Th th | /tʰ/ | An “aspirated” t (see below) |

| Tr tr | /tɕ/ | Like an English “ch” |

| U u | /u/ | Like an English “oo”, as in “shoot” |

| Ư ư | /ɯ/ | This vowel is very hard to pronounce. I give a detailed description below |

| V v | /v/ or /j/ | Like the English “v”, although southerners often pronounce it like a “y”. |

| X x | /s/ | Like the English “s”. |

| Y y | /i/ | Like the “ee” in the English “bee”. (Same as the Vietnamese “i”) |

As you can see, there's a lot to learn! Here are a few other things to note:

How Do You Pronounce “ư” in Vietnamese?

Of all the vowel sounds in Vietnamese, by far the one that English speakers find hardest to pronounce is “ư”.

Linguists call this the “close back unrounded vowel”, and if you go to Wikipedia you can hear a recording of it. My best explanation of how to pronounce it is this:

- Position your tongue and lips as if you were going to say an “oo” sound, as in “shoot”. Notice that your tongue is high and back in your mouth, and your lips are rounded.

- Without moving your tongue, spread your lips wide into a smile.

- Make a noise! With your tongue in the “oo” position and your lips wide, you should make a perfect “ư”

How Do You Pronounce “ê” and “ô” in Vietnamese?

In the table above, I told you not to “diphthongise” the “ê” and “ô” sounds. But what does that actually mean?

This is actually the same advice that's required when learning how to pronounce the “ê” and “ô” sounds in Portuguese, or the “e” and “o” sounds in Spanish. For example, see tip number 2 in this list of pronunciation tips I wrote for Spanish learners — the exact same point applies here.

Essentially, a Vietnamese ê is like the “ay” in “way”, and the Vietnamese ô is like the “oe” in “toe”. Except, when we say the words “way” or “toe” in English, we move our tongue throughout the course of the vowel. This is because the “ay” and “oe” sounds are actually two vowels combined into one; what linguists call “diphthongs”.

When saying ê and ô in Vietnamese, however, you mustn't move your tongue like this. Start saying the “ay” or “oe” sounds, but only say the first part; keep your tongue still.

“K” vs “c”, “G” vs “Gh”, and “Ng” vs “Ngh”

“K” and “c” sound the same in Vietnamese. How do you know which one to write? The rule is very simple:

- Before an i, y, e, or ê, write “k” – as in kem (cream)

- Before any other letter write “c” – as in có (to have)

Similarly, “g” and “gh” are pronounced the same, as are “ng” and “ngh”. The rules are the same for both pairs, and only slightly different from the k/c rule:

- Before an i, e, or ê, write “ngh” or “gh” – as in nghe (“to hear”) or ghe (“to hit”)

- Before any other letter write “ng” or “g” – as in Nga (“Russia”) or gái (“girl”).

Vietnamese Implosives

Two of the most tricky sounds in Vietnamese are the “b” and “đ” consonants. (Remember that “d” in Vietnamese, without the line through it, is nothing like an English “d”.)

“B” and “đ” aren't like the English “b” and “d” (although if you pronounce them in that way, you'll probably be understood). Instead, they're what's known as implosive consonants.

What does that mean? Well, according to Wikipedia:

Implosive consonants are a group of stop consonants … with a mixed glottalic ingressive and pulmonic egressive airstream mechanism. That is, the airstream is controlled by moving the glottis downward in addition to expelling air from the lungs.

Get it? I thought not. It's hard to explain. But you can start by listening to these clips to get an idea of what the “b” and “đ” sound like:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=47alW1vW9-E

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=edU6cGBXtTQ

The best way I have found to describe the Vietnamese “b” and “đ” is this: say a regular “b” or “d”, but as if you're breathing in rather than out.

That's not a physiologically accurate description of what's happening, but it's kind of what it feels like.

For a more detailed description of implosives (and other unusual sounds, including some that aren't found in Vietnamese), try this video.

The Difference Between ‘t' and ‘th' in Vietnamese

Another tricky thing for English learners of Vietnamese is the difference between the “t” and “th” sounds.

If you want to get a deep understanding, I suggest looking up the linguistic concept of “aspirated vs. unaspirated consonants”. I wrote a little about this in my article on the International Phonetic Alphabet.

For now, here's the basic idea: the Vietnamese t is pronounced a bit “harder” than an English “t”. By that I mean that it's less “airy”; sort of halfway between an English “t” and English “d”.

The Vietnamese th, on the other hand, is much “softer”. (In linguistic terms, it's aspirated.) Say the “t” sound, but with a bit more air behind it than you would for an English “t”.

One way to think about the Vietnamese “th” is to pronounce it like it's spelled. I don't mean pronounce it like an English “th”, which is something completely different – I mean “pronounce it like an English “t”, followed immediately by an English “h”.

Listen to native speakers, keep practicing, and you should pick up the difference fairly quickly.

Closing Your Mouth/Puffing Out Your Cheeks

There's one last thing to note. When you talk with Vietnamese people, you'll notice they sometimes puff out their cheeks when they speak. You'll notice this, for example, with the word không, which means “no”.

This happens with words that end in -ong, -ông, or -ung. The “ng” is still pronounced, but you simultaneously close your lips and make an “m” sound, too. So the full pronunciation of không is something like “kh – ô – ng – m”.

As for why the Vietnamese tend to puff out their cheeks in an exaggerated manner when they pronounce this sound, I have no idea. But do it yourself if you want to seem more convincing as a Vietnamese speaker.

You Can Learn the Vietnamese Alphabet!

This covers the basics of Vietnamese spelling and pronunciation — although, as we've seen, things really aren't that basic! There's a lot to take in.

However, if you work hard at it, I promise it'll pay off. In fact, as someone who has lived in Vietnam, I can tell you this: it's amazing how little Vietnamese you need to learn for the locals to be extremely impressed. So few người nước ngoài (foreigners) in Vietnam bother to learn any of the language at all that if you can even say (and pronounce) the absolute basics, Vietnamese people will treat you like a linguistic genius.

So I hope that the above guide is a useful starting point. Have fun as you learn the Vietnamese alphabet!

Social